Italy’s Most Stunning Mosaics from Rome to Ravenna to Sicily

Greeks and Byzantines get most of the credit for developing mosaics, but they did much of their greatest work abroad. In Italy, most visitors prepare for domes, sculptures, and paintings – and then find themselves mesmerized by a panel of tiny tiles depicting a cat’s whiskers, or a ceiling awash with gleaming stars.

Besides the concentration of Roman-era panels, Italy features the greatest repository of Byzantine mosaics in the world. Ancient Romans popularized floors of tesserae, creating works of astonishing technical and artistic innovation. Early Italian churches followed the Byzantine model with gleaming mosaic cycles, which survived long after Constantinople fell to the Ottomans. Domestic still-lifes, political propaganda, and patterned sheep are just a few of the surprises rendered in tile over the millennia.

Blending the boundary between architecture and art, mosaics are best appreciated in person. Although they can be found throughout Italy, a few spots stand out for the density and quality of their examples. Our guide organizes highlights by location, with a bit of context for each place.

Bay of Naples: Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the National Archaeological Museum

Rome: National Museum at Palazzo Massimo, Ostia Antica, Baths of Caracalla, Santa Costanza, Santa Pudenziana, Santa Prassede, Santa Maria di Trastevere, San Clemente, Santa Maria Maggiore

Ravenna: Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Neonian Baptistery, Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Arian Baptistery, Archiepiscopal Chapel, San Vitale, Sant’Apollinare in Classe

Venice: Santa Maria Assunta on Torcello Island, Basilica of St. Mark’s

Central Sicily: Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina

Palermo and Environs: La Martorana, Palatine Chapel, cathedrals of Cefalù and Monreale

Ancient Mosaics

Mesopotamians laid geometric mosaics in the third millennium BCE using colored stones, shells, and ivory. Later, ancient Greeks assembled pebbles into pictorial scenes, primarily on floors. During the Hellenistic period they switched to flat, regularly-sized pieces, while glass greatly expanded the range of colors.

As usual, Romans took the idea and ran with it, developing techniques to streamline fabrication and laying mosaic floors across their expanding empire. They called the pieces tesserae (from the Latin word for cubes and dice), and alternated sizes according to budget. Many floors feature a central section called the emblem, laid in tiny pieces of opus vericulatum (“worm-like work”), surrounded by larger squares forming graphic patterns.

Bay of Naples

Mount Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 CE preserved an incredible number of mosaics at Pompeii and Herculaneum. In the former, the House of the Tragic Poet has an excellent cave canem (“Beware of dog”), a popular design for thresholds.

Although most walls were covered with frescoes, mosaics were used for wet places like bathhouses and gardens. A rare vertical panel in Herculaneum’s House of Neptune and Amphitrite incorporates both marble and glass.

The more delicate panels were eventually transported to museums. The Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (a.k.a. MANN) tops the list of landmarks in Naples. Almost everything from Pompeii, Herculaneum, and nearby sites which required safe-keeping wound up here; even with many items on loan to other institutions around the world, the collection is staggering in its depth.

Probably the most famous panel is the immense Alexander Mosaic with roughly 1.5 million pieces. Other highlights include street musicians, a pair of very dramatic theater masks set against fruit, and a winged baby Bacchus riding a cross-eyed tiger.

Rome

Rome’s ancient mosaics are numerous but more scattered than in Naples. Many of the city’s big-ticket museums hold famous panels among their other works, such as the Capitoline Museum’s unbelievably life-like version of doves drinking from a bowl. It’s one of two widely-copied designs by Sosus of Pergamon, who also originated the trend for depicting scraps of luxury food ‘dropped’ on the ground in dining areas. In the Vatican Museum, one of these “unswept floor” (asarotos oikos) mosaics even has a perfectly-shadowed mouse nibbling away at a walnut.

National Museum of Rome: Palazzo Massimo

For a more extensive collection of mosaics (and fewer crowds), head to the Palazzo Massimo branch of the Museo Nazionale di Roma, next to the Baths of Diocletian. Its magnificent panels include a cat snagging a bird, Cupid riding a sea-goat, and a fruit-bedecked Dionysus who could have inspired Caravaggio.

Ostia Antica

Ostia Antica, Rome’s underrated alternative to Pompeii, has a wide array of mosaic floors in situ. It’s one of the best places to see the distinctive Roman black-figure-on-white-ground style. Reducing the palette to two colors made the designs economical while the high contrast adds drama.

Baths of Caracalla

The baths show the effectiveness of tiles for vast spaces, particularly the more graphic versions. In some places a distinctive leaf-checkerboard pattern appears to move.

Christian Mosaics in Rome

Christian art and architecture evolved in a world dominated by the Romans. While the shift in mosaics can seem abrupt, the transition from black and white floors in secular buildings to golden church walls took place over several centuries. In bathhouse complexes and palaces like Emperor Nero’s Domus Aurea, tiles moved beyond paving and onto walls, vaults, and even domes. Tesserae also adorned niches for sacred objects. For a time some mosaics even blurred the traditional divide between pagan and Christian subject matter, as evidenced by the Jesus-as-sun-god mosaic near the crypt of St. Peter’s in Rome. For more information, see our post on Rome’s Ancient Churches and Basilicas.

Santa Costanza

North of central Rome, the complex of Santa Costanza houses both pagan and Christian imagery. It began as a mausoleum in the fourth century, when funerary motifs often included vines and references to Bacchus (the god of wine). These mosaics were incorporated into the vault of a church erected not long afterwards.

A pair of apses retain their original mosaics, albeit with heavy restoration, including a very early depiction of Christ as ruler of the world. Perched on a blue globe and dressed in robes of royal purple and gold, he hands keys of power to a supplicating Peter.

Santa Pudenziana

Although its origins are still being investigated, this is likely the oldest continuously-used church in Rome. The building was one of the original tituli, houses where Christians met to avoid the notice of hostile authorities. In the fourth century, the existing structure was transformed into a basilica. Most of what remains is a mixture of renovations and restorations over the centuries, with a mosaic in the apse dating to roughly 390.

Here the continuity between Imperial and Christian Rome is unmistakable. Early depictions generally represented Christ symbolically, for example as a lamb. Here he is not only human but seated on a throne, wearing senatorial garb and posed as a classical Roman teacher. His flowing hair and beard echo depictions of Zeus/Jupiter, and the imperial staff has become a cross.

Santa Maria Maggiore

One of the four major papal basilicas, Santa Maria Maggiore preserves mosaics from the fifth and 13th centuries. The early panels in the nave and triumphal arch, as well as the later apse, can be difficult to make out from afar in the dim light. A supplementary ticket allows access to the upper loggia, with closer views of its late Medieval mosaics.

Santa Maria di Trastevere

This fourth-century church features mosaics inside and out. The meaning of the facade’s golden panel continues to elude historians. Although most of the works date to the 12th and 13th centuries, the Sacristy holds a pair of first century mosaics from Palestrina depicting birds and a seascape.

Santa Prassede & San Zeno Chapel

Behind its unassuming façade, the Santa Prassede hides some of Italy’s most spectacular early Christian mosaics. Pope Paschal commissioned the church in the ninth century; the adjoining San Zeno chapel is a mausoleum for his mother. Both the apse and the chapel are plastered with meticulously crafted scenes using imperial symbolism to promote Christianity. For instance, the apse shows Christ receiving a Roman-style wreath of victory.

San Clemente

Mosaic floor panels provide continuity between the layers of this church, which spans more than a thousand years. As glass tesserae moved to walls and ceilings, inlaid stones of various colors became the standard for floors.

The ancient Roman technique of opus sectile evolved into a distinctive style called Comatesque. San Clemente has a magnificent example, with ribbons of tiny squares looping over, under, and around one another ad infinitum. Meanwhile the 12th century walls feature some of the city’s best Byzantine mosaics. Instead of religious figures, the apse features a variation on the Tree of Life, with densely spiraling vines symbolizing the living Church.

Ravenna

With the most spectacular collection of Byzantine mosaics anywhere, one might expect Ravenna to feature more prominently in tourist itineraries. The city sees its fair share of crowds – but not nearly as many as one might expect from the quality of its monuments. Visiting Ravenna’s seven mosaic-drenched interiors makes an exhilarating day, even for those leery of too many churches. The UNESCO-listed sites are full of experimentation, as the Western world transitioned to a new era in politics, religion, and art.

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia

The earliest of Ravenna’s monuments (425-450) commemorates one of its most remarkable rulers, although she was not actually buried here. Galla Placidia helped the city thrive among imperial Rome, Byzantine, and Gothic powers. She was also the first secular leader to put her own likeness next to the Christian figures on church walls.

A constellation of stars against a nighttime sky may be the most memorable of the tiled compositions covering nearly every surface. The deep blue background echoes aquatic motifs, and contrasts beautifully with the Byzantine windows of glowing alabaster. Gold, symbolizing divine light, is prominent here, though it wouldn’t become the norm for backdrops until the end of the century.

Neonian Baptistery and Arian Baptistery

As various groups debated Christianity’s development, artists depicted Jesus in different ways. A pair of baptisteries illustrates how ideological differences played out in Ravenna’s mosaics. The first was constructed by Bishop Neon between 450 and 475 and is considered the best-preserved early Christian baptistery in the world. The second was built by King Theodoric a few decades later; it was neglected when the Arian doctrine was stamped out.

The Baptism of Christ, as seen in the Neonian Baptistery (left) and the Arian Baptistery (right)

At first glance, the imagery in both spaces looks similar, especially to modern viewers unaccustomed to seeing Jesus without clothing. (The church didn’t forbid nudity in art until the Renaissance.) However, the Neonian Baptistery depicts him as a bearded man in the Roman Catholic tradition, while the Arian version shows a fresh-faced youth.

Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

Ravenna hit its peak during the reign of Theodoric, from 493-526. The highly-cultured king built Sant’Apollinare Nuovo as his palatine (royal) church with a spacious scale and liberal amounts of glittering mosaics. Holy figures line both sides of the nave. The bottom row features female martyrs garbed in exquisite fabrics on one side and male martyrs in delicate sandals on the other.

When the Byzantines took control of the city in 541, they teamed up with the Catholics to suppress Theodoric’s legacy. At the end of the nave, mosaics depicting his palace were altered: portraits of the king and his associates were replaced with golden bricks and curtains. (A few vestigial hands can be seen floating between the columns.) A bird’s-eye panorama of the city shows what it looked like 1500 years ago.

Archiepiscopal Museum and Chapel of Saint Andrew

The old bishops palace has been converted into a museum whose artifacts include sections from the original cathedral. Within the building, a small chapel survives from Theodoric’s reign. The chapel’s centerpiece features symbols of the Four Evangelists (Lion, Ox, Angel, and Eagle) surrounding Christ’s initials, while birds (both exotic and local varieties flutter around the outside.

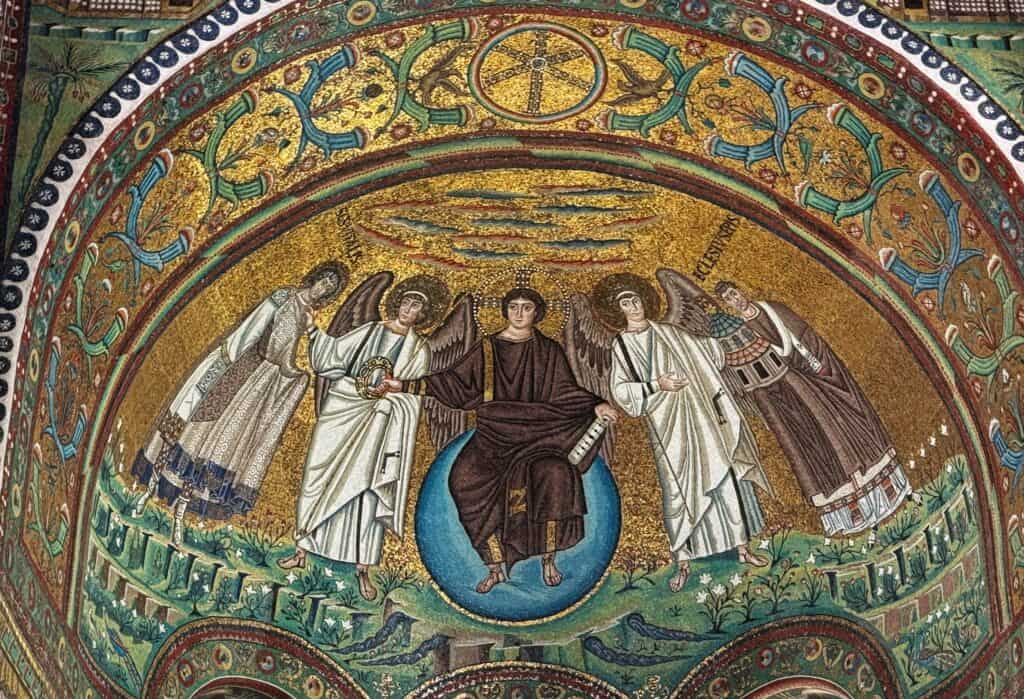

San Vitale

This church is Ravenna’s most opulently Byzantine monument. Along with Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia, it represents the pinnacle of architecture and mosaics under Emperor Justinian. Jewel-like tesserae drape across surfaces like swathes of divine cloth.

Master mosaicists adjusted the angle and spacing of each tiny square to create maximum sparkle, factoring in light conditions in various parts of the building. A pair of especially-famous panels depict the emperor and his wife Theodora, each haloed and surrounded by religious and secular attendants in sumptuous fabrics.

Sant’Apollinare in Classe

The old Roman port of Classe, adjacent to the settlement at Ravenna, got its own major church in the mid-sixth century. It was constructed at the same time as San Vitale, with funding from the same local banker. Unlike the Vitale’s centrally-oriented Byzantine floor plan, however, Sant’Apollinaire in Classe is a classic basilica with a long nave. The architecture is more spare here, with mosaics limited mostly to the end of the building. Pastoral greenery dominates the wide apse, with slivers of clouds squeezed into the golden sky.

Venice

Early settlers of the lagoon allied themselves with Byzantium, and Byzantine architecture deeply influenced Venice. Thanks to its local glass fabrication, the city was a natural candidate to take over production of mosaics as the eastern empire crumbled. By then, however, tastes were turning in favor of painting – and the later panels of tesserae never quite matched the passion and artistry of medieval times.

Torcello Island

A boat ride out to the lagoon’s original settlement Torcello feels like stepping back in time. 11th-century mosaics in the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta are the oldest and most characterful in greater Venice. A slender strip of a Madonna commands the apse, with a gaze both steely and gentle. She faces a phantasmagorical Last Judgement in which grinning blue devils and a naked sea goddess watch angels rescue souls from the maws of sea-serpents.

St. Mark’s Basilica

Eight centuries of mosaics in nearly every material cover most every surface of Venice’s most famous and most grandiose church. They compete for attention with a treasure-house of carvings and relics, and the overall experience can be a bit overwhelming.

The oldest mosaics date to the 11th century, including the niches in the narthex (entry court) as well as the inlaid-marble floor. Some of the most acclaimed works, like the left-most panel on the main facade, were made in the 13th century. Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, and other famous painters were brought in to design replacements for some of the mosaics in the 16th century. Ongoing renovations and repairs over the years saw a decline in the quality of execution.

Central Sicily

Ancient Romans used Sicily primarily as a source of grain, with governors overseeing vast agricultural estates from luxurious villas. The island’s older mosaics are therefore fairly scattered.

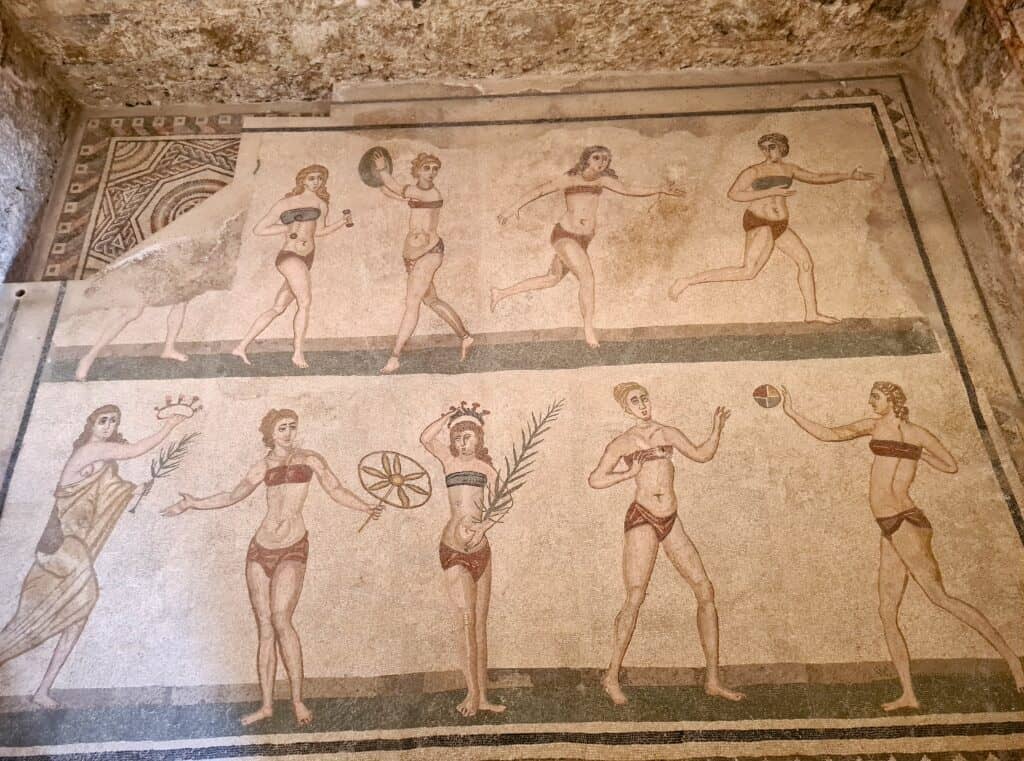

Villa Romana del Casale

In terms of quality, quantity, and diversity, the UNESCO-listed Villa Romana del Casale is generally considered to have the greatest set of Roman mosaics in situ anywhere. Located just outside the town of Piazza Armerina in central Sicily, the fourth-century complex was built as a hunting lodge for a senator or perhaps Emperor Maximian. Among the scenes depicting battles with animals, the Great Hunt mosaic portrays exotic animals being loaded and unloaded from a ship. Feathers and fur are no match for a bikini, however: the maidens exercising in the site’s most famous panel look ready for the beach.

Palermo and Environs

Sicily’s Greek and Byzantine heritage merged with Islamic and Latin/European traditions when Normans from northern France turned the island into an independent powerhouse. The conquerors’ philosophy of inclusion took physical form in a series of unique churches.

Palatine Chapel

In 1140, a decade after beginning his personal chapel within Palermo’s royal palace, Norman King Roger II brought a team of mosaicists over from Istanbul to decorate it. They trained a new generation who added the panels with Latin (rather than Greek) inscriptions under William I a few decades later. Their gleaming golden intricacy complements the ornate wooden carvings by Arab artisans.

Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio (La Martorana)

Founded by the Normans’ brilliant admiral in 1143, this fascinating little church in central Palermo retains some of its original mosaics, even after a Baroque remodel and a few awkward restorations. Exquisitely detailed and incredibly preserved, they rival even the cathedrals of Cefalù and Monreale, albeit on a smaller scale. One notable panel depicts Jesus coronating Roger II, indicating Sicily’s independence from the Papacy.

Cefalù Cathedral

In the nearby town of Cefalù, Roger II and his craftsmen transferred the Palatine Chapel’s revolutionary fusion to a larger, more public scale. Within the cathedral’s Norman-French structure, Byzantine mosaics represented the Eastern Orthodox tradition of Sicily’s Greek population, while Islamic-style carvings and friezes represented local Arabs.

Among the mosaics, the apse stands out for its Christ Pantocrator (“All-Powerful”), arguably the best in the world. Byzantines had developed a convention of using size and positioning to indicate a subjects’ level of divinity, hence the tradition of an outsized Jesus looming from the main apse. This one is not only huge, but also has an expressiveness to rival great paintings.

Monreale Cathedral

On a hilltop overlooking Palermo, the cathedral complex of Monreale may be the best place to experience mosaics anywhere. William I used his grandfather’s cathedral in Cefalù as a model for the one in Monreale, but increased the scale.

The interior is over 140 feet (43 meters) high, with nearly two acres (7,000 square meters) of tile. Although the Christ Pantocrator here isn’t as expressive as the one in Cefalù, the overall effect of the mosaics is staggering.

Ample windows allow sunlight to play across vast expanses of individually-sparkling tesserae. It’s hardly surprising that the pope immediately declared Monreale the greatest work of architecture since antiquity.

Further Reading

A Guide to Istanbul’s Byzantine Architecture

Norman Sicily: The Cathedrals of Cefalù and Monreale

A Guide to Palermo’s Architectural Curiosities