Istanbul’s Topkapı Palace – Is it Worth the High Ticket Price?

Not many places in the world have acquired as much mystique as the Topkapı Palace, the city-within-a-city which formed the core of the Ottoman Empire. Unfortunately, it takes some effort to reconcile the palace of legend with today’s complex, where shuffling crowds and astronomical ticket prices may feel less than sublime.

For those steeped in stories of Topkapı and its inhabitants, no trip to Istanbul would be complete without a pilgrimage to the palace. For others, it may not be worth the investment of time and money. To help with the decision, our guide covers the highlights of Topkapı and advice on planning a visit – as well as some alternate places to experience Ottoman architecture.

Table of Contents

Planning a Visit to Topkapı: Tickets, Opening Hours and Crowds

Topkapı Palace Layout and Highlights

Alternatives to Topkapı

Further Reading

Planning a Visit to Topkapı

Tickets

In recent years entrance fees for Turkish landmarks have shot up at a rate far beyond other countries, and Topkapı Palace is the most expensive monument in Istanbul. In 2025, a standard combo ticket costs 2400₺ (about EUR €54 or USD $60); for perspective, that’s roughly triple the price of the Alhambra, the Vatican, or the Louvre. (Note: Turkish citizens pay significantly less.)

Along with prices, ticket policies seem to be constantly in flux. At present, non-Turkish visitors can only buy the combined ticket for the main palace and harem plus the Hagia Irene. Although a number of websites attempt to pass themselves off as official ticket vendors, the authorized source for information is Istanbul’s museum network. Currently this site sells only 5- or 7-day museum passes rather than tickets to individual sites like Topkapı. Anyone who doesn’t want to invest in a multi-day pass can buy entry tickets on-site. Arriving in mid-afternoon, we didn’t have to wait for more than a few minutes when we bought our tickets on the spot. Note that pricier “skip-the-line” tickets allow entry within a particular timeslot, but everyone still has to queue for security checks.

Opening Hours and Crowds

Past the ticket barrier, many spaces have a line to enter and serious crowds within. In the Harem, congestion in tight spaces plus a disorienting layout can feel claustrophobic.

Careful timing makes a tremendous difference. In a site as large as Topkapı Palace, it’s best to decide on a few priorities and be prepared to skip around. Morning visitors might want to go straight to the Harem or Inner Treasury; in the afternoon, these hotspots are best saved for the end of the day when crowds have thinned.

Topkapı Palace Layout and highlights

Topkapı occupies one of the world’s greatest pieces of real estate, atop a hilly promontory overlooking the juncture of two continents and three major bodies of water. The Great Palace of Constantinople was mostly rubble when the Ottomans began construction of Topkapı in 1453. With near-constant additions and alterations over the subsequent centuries, no single ruler or period dominates. The dense array of buildings includes Persian- and Rococo-influenced styles as well as classical Ottoman works.

Topkapı is made up of four main courtyards, plus the harem. Like most Islamic palace complexes, the site progresses from public areas on its edges to increasingly intimate and restricted spaces further in.

First Court

Imperial processions passed by the Fountain of Ahmed III before entering Topkapı through the Imperial Gate to the First Court. Here the Sultan’s Janissaries (elite troops) guarded the palace’s outer precincts. Today anyone can enter the space, where cypress-lined paths cut diagonally between buildings both ancient and modern. Besides the former Mint, this section contains ticketing facilities as well as the Hagia Irene, the sole pre-Ottoman building within the palace. Some think it was completed before Constantine’s death, making it one of the oldest surviving churches anywhere.

Unlike most churches in Istanbul, the Hagia Irene was never used as a mosque. Stripped down to its bones by looters during the Fourth Crusade and later the Ottoman conquest, the structure served as an armory for most of the following centuries. Scaffolding and tarps obscured much of the interior’s main space when we visited, including the unusual elliptical dome.

Second Court

Beyond the ticket barrier and Middle Gate, the Second Court’s park-like grounds are surrounded by the empire’s administrative machinery, from the all-important Divan (Council) Chamber to an entire set of kitchens dedicated to confectionery arts.

Master architect Sinan redesigned the kitchen wing after a major fire in 1574. Two sections display the palace’s renowned collection of decorative objects and servingware. The third part contains the confectionary kitchen, with domes in various shapes for conducting the air efficiently.

The Harem

The palace’s notorious Harem runs along the side of the second and third courts. It’s a bewildering warren of cramped and sometimes dark spaces with momentary eruptions of colorful tiles. Originally, the labyrinthian layout provided extra security for the Sultan’s family and their retainers. Only a fraction of the six-floor complex is open to the public today, but the number of spaces is still overwhelming – especially if you try to keep track of the elaborate social hierarchy they housed.

Then as now, visitors enter the Harem via the Courtyard of the Eunuchs, named after the castrated men who guarded and advised the women and children. Several hundred concubines lived in the Harem at any given time, serving the royal family. Although both the eunuchs and concubines began as slaves, their ultra-structured society provided paths for advancement. Architectural grandeur reflected status, which increased moving further towards the rear of the complex.

The Apartments of the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother) were the heart of the Harem. None of the women’s apartments match the opulence in those of the royal men, even though the Sultan’s mother or wife often dominated the empire’s rule.

Due to fire and later renovations, little remains of the work by Mimar Sinan in the Harem. A tantalizing glimpse remains in the Privy Chamber of Murad III. Restored to its full glory, it’s often called the most beautiful room in Topkapı. One of the most famous details is a marble-inlay wall fountain which created a pleasant burbling noise – and hindered eavesdropping.

Adjacent to the Privy Chamber of Murad III is the Courtyard of the Favourites, residence of the Sultan’s wives and mistresses. The exquisite Twin Kiosks housed the Sultan’s sons, but unfortunately their interiors were closed when we visited.

Third Court

Past the Gate of Felicity, the Third Court housed the Sultan and his pages. Nowadays the rooms display his many possessions, including the Imperial (Inner) Treasury and the Chamber of the Holy Relics. Both rooms were packed when we visited. In the former, visitors clutched one another in the darkness between displays of egg-sized emeralds and other jewels.

After conquering Egypt, the Ottomans laid claim to the Muslim world’s three holiest sites as well as the defeated Mamluks’ collection of sacred relics. Topkapı’s original Privy Chamber was expanded into a complex to house items such as the keys to the Ka’ba. (Meanwhile the sultans eventually built new bedchambers in the Harem.) While many monuments in Turkey now have divisions between religious and secular space, the Sacred Trust permits everyone to reflect upon the artifacts together.

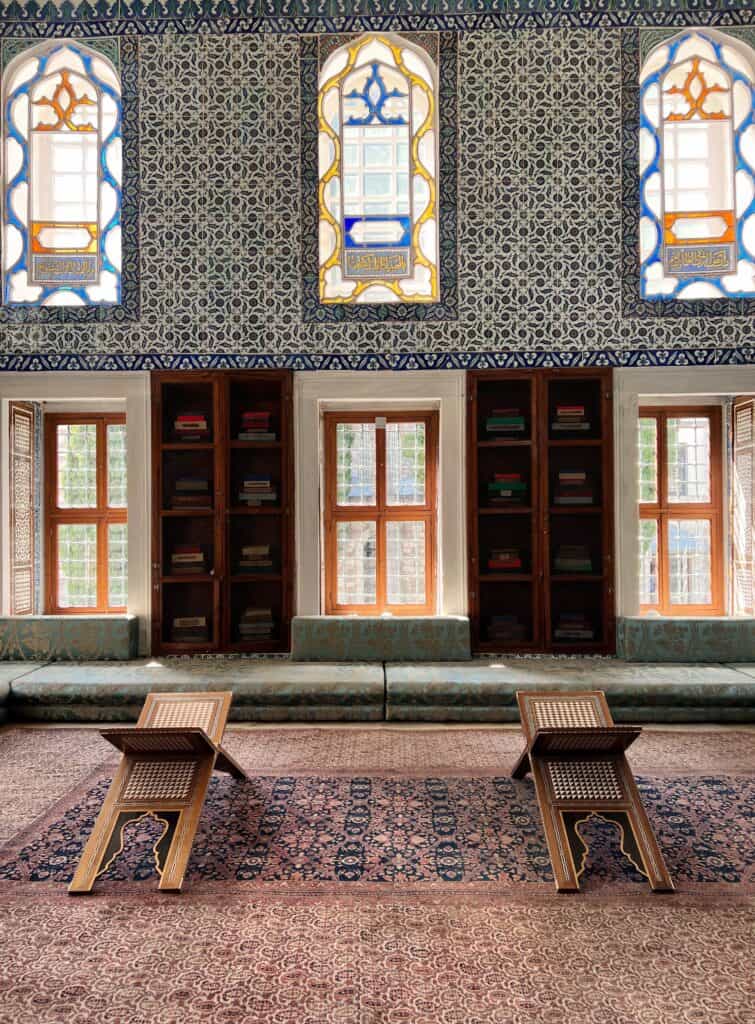

While the Audience Chamber felt smaller than we expected from historical descriptions, the library in the center of the garden was a lovely surprise. The free-standing structure – built for tulip fanatic Ahmed III – is an example of the ‘Tulip Period’ when French Rococo and Persian Safavid influences mixed with classical Ottoman styles.

Fourth Court

At the end of the palace, a series of showstopper pavilions use ornament to create a uniquely Ottoman version of classic Islamic garden rooms. One of them may very well be the world’s most beautiful Circumcision Room.

In the nearby Yerevan and Baghdad Kiosks, stained glass lattices and tile panels hover over built-in sofas and inlaid doors, all topped by intricately-painted domes with golden accents. Some consider these to be the ideal Ottoman rooms. The Marble Terrace connects them to the little İftar Kiosk, with a gilded roof reminiscent of Mughal structures. From here, the Sultan could sit and watch games in the gardens below or contemplate the Golden Horn.

Later structures exhibit increasing levels of Western influence. The wooden Terrace Kiosk by the Tulip Garden was rebuilt in 1752 in an Ottoman version of Rococo, but the palace’s final additions (circa 1840) appear to have adopted European style wholesale.

Alternative Sites

Topkapı Palace does not have a monopoly on lavish architecture. One of the best ways to experience the Ottoman world is to visit Istanbul’s unique mosque complexes, particularly the ones designed by Mimar Sinan. Generally considered to be one of the greatest architects of all time, he surrounded soaring domes and Iznik tiles with serene courtyards, all of which are free to enter today. We’ve chosen a few centrally-located favorites as a sampling of his extensive work; for more information see our guide to Sinan’s architecture in Istanbul.

Note: the Blue Mosque, designed by Sinan’s student, also deserves a spot on any short list of Ottoman monuments. However its popularity means long waits to get in. For more information, see our overview of Istanbul’s architecture.

Süleymaniye Complex

Sinan’s design for the Süleymaniye announced a fully-fledged Ottoman architecture which could hold its own against the Hagia Sophia. Designed to preside over the city from all vantages, the mosque crowns its hilltop. Enormous in both scale and variety of buildings, the Süleymaniye complex once housed five madrasas, a hospital, hospice, elementary school, guest housing, kitchens, baths, and numerous shops.

Some of the site’s larger pieces famously came from the Hippodrome. Iznik tiles, with their innovative production and uniquely Ottoman patterns, make their first appearance here. Later, Sinan added mausoleums for Suleyman and his wife Roxelana. The gardens wrapping around the central mosque include a promenade with expansive city views. It’s a beloved but surprisingly uncrowded place for locals and tourists alike to relax.

Rustem Paşa Mosque

In the thick of the old spice market, an unobtrusive set of stairs leads to a secret world. The mosque memorializing Grand Vizier Rustem Paşa sits right on top of a block of shops, behind a tiny courtyard where plant motifs on tiled wall panels create an illusory garden. Inside is a riot of color and light, with over 80 patterns of tile coating nearly every surface.

The city of Iznik was just hitting its golden age of tile production, with innovations such as deep red underglaze and a fresh, uniquely Ottoman series of patterns. In this mosque Sinan let the tiles take center stage. He wisely restrained the rest of the building to the same palette: everything harmonizes with the glowing white, cobalt, turquoise, and red. Enter via a flight of stairs at the corner of Makheme Sk. and Hasırcılar Cd. Inside the mosque, don’t miss the upstairs gallery.

Sokollu Mehmet Paşa Mosque

For the mosque commissioned in 1571 by the Grand Vizier and his wife, Sinan made superb use of a cramped, sloping site. Multiple levels establish different zones while maintaining an open feel and creating an ever-changing sequence of views as one moves through the complex. In order to add grandeur to the tiny space Sinan paved the courtyard in marble, a convention normally reserved for sultanic projects.

Many consider the petite Sokollu Mehmed Paşa to be Sinan’s best interior, with “the finest single wall of tile ever created by Iznik”. The ornamentation is lavish but never excessive, and sensitive restoration preserved the original paintings in several places. The entire building serves as a jewel box for precious fragments from the Ka’ba stone in Mecca. In spite of its location just below the Hippodrome, the mosque sees surprisingly little traffic.

Further Reading

Elif Shafak’s novel The Architect’s Apprentice paints a vivid picture of life in the Ottoman court as told from the point of view of Sinan’s apprentice.

For more on Istanbul, see our posts:

A Guide to Sinan’s Ottoman Masterpieces in Istanbul

A Guide to Istanbul’s Iconic Architecture