A Guide to Ancient Architecture in Rome

Everyday language shows the extent of Rome’s contributions to the built world. “Capital” and “capitol” come from Capitoline Hill. “Palace” originated in the luxurious residences on the Palatine. The forum, basilica, circus, colosseum, and countless other kinds of structures began here. A remarkable number of originals still survive while others inspired newer constructions. From gushing fountains to soaring concrete domes, ancient Rome feels uncannily familiar.

Guides to the Eternal City generally split it into ancient and post-Renaissance monuments, but in Rome the past and the present often mix together. From apartments in a 2,000 year-old old theater to a temple incorporated into the Stock Exchange, the modern city brims with antiquity. We’ve curated a guide to the highlights of central Rome, organized by building type for context. All sites are marked on our Google map.

Table of Contents

Roads, Bridges, and Aqueducts: Clivus Scauri, Appian Way, Pons Fabricius, Pons Aelius (Ponte Sant’Angelo), Park of the Aqueducts (Aqua Marcia and Aqua Claudia)

Forums, Triumphal Arches, and Basilicas: Forum Romanum, Imperial Forums, Arch of Titus, Arch of Severus, Arch of Constantine, Arch of Janus, Basilica of Maxentius

Temples and Mausoleums: Temple of Hercules Victor, Temple of Portunus, Pantheon, Temple of Hadrian, Mausoleum of Hadrian (Castel Sant’Angelo)

Baths, Theaters and Stadiums: Baths of Caracalla, Baths of Diocletian, Theater of Marcellus, Colosseum, Circus Maximus

Residences: Domus Aurea, Palatine Hill and the Houses of Livia and Augustus

Roman Construction

Romans considered themselves practical types who adopted the more sophisticated cultures of the Greeks and Etruscans. While they preserved stylistic elements like fluted Ionic columns and Corinthian capitals, the upstart civilization wound up changing architecture on a much deeper level. Instead of continuing the simple post-and-lintel system, Romans exploited the potential of arches, vaults, and domes. They also switched from solid blocks of heavy material to brick covered with lightweight veneers of stone. The key to it all was concrete.

Roman concrete mixed with volcanic ash from Mount Vesuvius is considered superior to its modern counterpart. By varying the ingredients, ancient engineers developed formulas which hardened over time or under water. This allowed Romans to build on a huge scale with unprecedented speed and economy. Suddenly it was possible to design spaces according to their function rather than the limits of the construction material.

Roman Roads, Bridges, and Aqueducts

Clivus Scauri

This diminutive street may have begun as a track during the Stone Age, making it already thousands of years old when Rome began in the eighth century BCE. Today the Clivo di Scauro runs from the base of the Palatine Hill up to the top of the Caelian Hill. Ancient Romans called it the Clivus Scauri: clivus means “slope” in Latin, while Scauri likely referred to a prominent family. A striking set of ancient brick arches guides visitors to Case Romane del Celio, where some late Imperial homes feature striking frescoes and important early Christian artifacts.

Appian Way

Once Romans subdued the region around their fledgling city, they needed a way to move troops down the peninsula. In 312 BCE, Appius Claudius completed the first section of the iconic road which would eventually stretch all the way to the port of Brundisium (Brindisi). The Via Appia began a tradition of impeccably-crafted transportation routes, usually running arrow-straight with regular milestones and stations for travel-related services. It was likely the first Roman road made with lime cement, topped by a near-seamless layer of interlocking stones and tilted just enough to drain water off the sides. An ancient poet called it the regina viarum, or Queen of Roads.

Since burials were prohibited within the city, the first few kilometers of the Appian Way are lined with tombs, mausoleums, and catacombs. Nearby, the Roman elite found refuge from the urban center in large estates such as the Villa of Maxentius. The best section to visit starts at the catacombs of San Sebastiano and runs south (away from the city center).

Pons Fabricius (Ponte Fabricio)

Along with arches and concrete, Romans used innovative construction techniques to advance civilization. They revolutionized bridge-building by using sealed baskets called cofferdams to create dry pockets underwater. This allowed them to install stone piers to support a crossing above. Legend has it that ancient Roman engineers had to sleep under their own constructions as a guarantee of their stability. For more information, see our guide to Rome’s bridges.

The Ponte Fabricio (Pons Fabricius) is the oldest functioning bridge in Rome and the third-oldest in the world. Named after the curator viarum (head of roadworks) Lucius Fabricius in 62 BCE, it later became known as the “Jewish Bridge” due to the nearby Ghetto. Apart from replacements of the brick facing, the entire structure is original. A statue of four-faced god Janus was added to each end in the 14th century.

Pons Aelius (Ponte Sant’Angelo)

Arguably the most famous of Rome’s bridges, the Ponte Sant’Angelo (Pons Aelius) has been memorialized in countless works of art, including The Divine Comedy. Three of the five arches date to 134, when Emperor Hadrian had the bridge built next to his new mausoleum (today the Castel Sant’Angelo). Centuries later, the bridge formed part of the traditional pilgrimage route to St. Peter’s.

Park of the Aqueducts

Rome’s marshy environs didn’t include much by way of fresh water. By 312 BCE, the city’s first aqueduct supplied a fountain at the Forum Boarium (cattle market). Eventually no fewer than 11 aqueducts would supply the population of over a million with water for drinking and washing – with enough left over for farming and industrial needs like powering mills and mining.

Many aqueducts were destroyed or abandoned in the Middle Ages, but some stretches remain in the Parco degli Acquedotti. These include the Aqua Marcia (144-140 BCE), which was the longest span of arches to carry water into the city, and the Aqua Claudia of 38-52 CE, which was the most ambitious aqueduct. The vast public park sits next to a golf course in the suburbs, near the legendary Cincecittà film studio. The park’s many cinematic appearances include the opening shot of La Dolce Vita. For visiting information, see the official website.

Roman Forums, Triumphal Arches, and Basilicas

Forum Romanum

Rome’s original forum occupies the valley between the sacred Capitoline Hill and the residential Palatine Hill. It grew from a place for villagers to gather and trade into a sprawling hub of civic, commercial, and religious activity. This messy, vibrant heart of the city doubtless assaulted the senses during its heyday. Today the site requires more than a little imagination to fill in the buildings and mentally replace the trousers with togas. Although it’s possible to speculate where some of the more famous events took place, most of the physical remnants here date to later centuries.

Imperial Forums

When the Republic grew into an Empire, the old forum simply wasn’t big enough. Successive rulers added ever-larger complexes for administration buildings to the north (towards the Colosseum). Today the area is dominated by Mussolini’s huge road running right through the ruins. The Forum of Caesar is adjacent to the old Mamertine prison; across the pedestrianized boulevard lies the sprawling Forum of Trajan as well as complexes built by Augustus and Nerva.

Arch of Titus

Romans traced the celebration of major military victories back to legendary city founder Romulus. Emperors continued the Republican tradition of parades featuring proud soldiers, humiliated prisoners of war, re-enactments of key events, and displays of all the loot. Processions culminated with a march along the Via Sacra (Sacred Way) through the old forum to the temples on the Capitoline Hill. Later, triumphal arches would be erected along the route for posterity.

Ten years after Vespasian and his son Titus put down a rebellion in Palestine, their successor Domitian commissioned an arch at the Via Sacra’s highest point. Its deeply-carved reliefs include early examples of humans and divinities mingling, such as the goddess Victory crowning Titus. There are also depictions of treasures from the Temple of Jerusalem, such as a menorah which would later serve as the model for the emblem of Israel. The arch itself inspired monuments around the world from Paris’s Arc de Triomphe to the India Gate in New Delhi.

Arch of Septimius Severus

This triple arch sits at the end of the Via Sacra, where the forum meets the Capitoline Hill. The structure was built in 203 CE to commemorate victory over the Parthians, a perennial Roman foe located in modern-day Iran and Iraq. It originally had a huge gilded bronze statue on top which was melted down and recycled in the Middle Ages. Although it’s one of the most spectacular examples of its kind, the arch is probably best known for a disfigurement: Emperor Caracalla had his brother executed and tried to erase his name from the upper level inscriptions.

Arch of Constantine

The Arch of Constantine was situated at a prime spot, right where the Via Triumphalis turns toward the old Forum and sacred temples of the Capitoline. The last and largest of the triumphal arches, it’s a mash-up of its predecessors. Erected just after Constantine’s victory at the Milvian Bridge battle in 312 CE, the structure uses not just the form but actual pieces from earlier monuments. The emperor had the heads of his “good” predecessors chiseled off and replaced with his own likeness.

Arch of Janus

Rome’s only quadrifrons, or four-sided arch, is one of the city’s most curious structures. It’s scaled like an enormous triumphal arch, but no one has been able to decipher why it was built. The core of brick and pottery shards was covered with spolia (marble recycled from other buildings) during Constantine’s reign in the early fourth century. Statues which filled the 48 niches have long since disappeared, but some decoration remains on the interior. In the Middle Ages, it was converted into a fortress.

19th century “conservationists” removed the entire upper section in the belief that it wasn’t original – hence the awkward, truncated appearance today. A car bomb exploded near the arch in 1993, furthering its general decay. Several restoration projects later, it’s unclear when the fence isolating it will be removed. For more information, see our post on the Forum Boarium.

Basilica of Maxentius

As the template for churches in Europe and across the globe, Roman basilicas became one of the most important building types in history. They evolved from the Greek stoa, an arcaded hall flanking the public square. Basilicas developed into a distinctive form, with a pair of smaller aisles flanking a long central area. Columns defined the sections without closing them off, while light streamed in through high windows. Magistrates presided from elevated platforms in the rounded ends (apses), with doors in the middle of the building. Christians later shifted the main entry to one end.

Emperor Maxentius began the city’s last secular basilica around 306. His successor Constantine completed it seven years later – and then adopted the form for the earliest Christian Churches. The enormous structure largely collapsed in later earthquakes, but the remaining side aisle would become a major influence on Renaissance architecture. Many of its statues were moved to the Capitoline museums, while the sole supporting column to survive now stands on the Piazza di Santa Maria Maggiore.

Roman Temples and Mausoleums

Temple of Hercules Victor

Rome’s oldest building is a monument to its Republican years – before the megalomaniac emperors – and a tribute to the refinement of Greek culture. In a city where pomp and grandeur reigned supreme, this little building holds its own by virtue of its elegant lines. The Temple of Hercules Victor also remains remarkably intact, even compared to Roman structures built hundreds of years later.

The temple’s origins are debated, though one theory links it with second-century BCE general Lucius Mummius Achaicus, who conquered much of Greece. Other than its circular form, its most distinctive aspect is the pure Greek style, right down to its walls of solid marble imported from Attica. Most structures in Rome adapted Hellenistic architecture rather than copying it outright, especially when it came to using stone. Pragmatic Romans preferred to build with lightweight, locally-available materials like volcanic tufa and brick, limiting marble to a thin layer on top. For more information, see our post on the Temple of Hercules Victor.

Temple of Portunus

The old Forum Boarium (cattle market) holds another small-but-mighty temple right by the Hercules Victor, this one dating to around 100 BCE. Given its location by the docks, scholars now associate it with Portunus, the god of ports, gateways, and livestock. Merchants could make last-minute offerings for their outgoing merchandise, while incoming products could be conveniently blessed en route.

Like most Roman temples, it follows the Greek model of a rectangular cella holding the god’s statue, surrounded by a colonnaded walkway. In an interesting variation, the Portunus features an enlarged interior, with the side and rear columns halfway embedded in the walls. The layout preserves the illusion of an arcade within a smaller footprint, and would serve as the model for the Maison Carrée in Nîmes. For more information, see our post on the Forum Boarium.

Pantheon

The granddaddy of all domes stands out from anything built before or since. At just over 43 meters (142 feet), the hemisphere spans more than twice the distance of any known precursors. It still holds the record for the widest masonry dome built without reinforcement. And in spite of its tremendous influence, the Pantheon still feels unique after 1,900 years. The dome is all but invisible from outside, which makes walking inside a visceral surprise.

The site’s first temple, built by Marcus Agrippa in 25 BCE, had no dome. A century and a half later, Emperor Hadrian completed the current version. The Pantheon’s dome works because the mass is concentrated in specific places. It’s thicker at the bottom: 23-meter foundations taper to a thin ring at the top. Travertine is used for the base, with terracotta in the middle, and lightweight volcanic tufa and pumice on top. Roman engineers also developed a lattice system to create ribs with light areas between them, resulting in the iconic indented squares called coffers.

The all-encompassing dome is a perfect form for a temple dedicated to all gods (pantheon); later efforts to convert it to a Christian church barely touch its grandeur. No one knows for certain how it was decorated, and whether the coffers were stuccoed and painted or coated with bronze. Legend has it that lighting the space with candles conducts enough heat to evaporate rain falling through the oculus. For more information, see our post on Roman domes.

Temple of Hadrian

Traditional Romans distrusted leaders who claimed a divine right to rule – but as the republic became an empire, other influences crept into the city. First emperor Augustus initiated a tradition of associating himself with the gods, and deifying members of the imperial family soon became commonplace. Antonius Pius consecrated a temple dedicated to his predecessor Hadrian in 145 CE. Today eleven imposing columns and a partially-reconstructed entablature remain, effortlessly dominating the Piazza di Pietra. One side of the interior (cella) wall also survives as part of the Stock Exchange building.

Mausoleum of Hadrian (Castel Sant’Angelo)

From catacombs to columbariums, one could dedicate an entire trip to the architecture of the dead in Rome. The most monumental might be the Castel Sant’Angelo, which began as a mausoleum for Emperor Hadrian. Built between 134 to 139 CE, it’s a mere decade younger than the Pantheon – and its continuous use is well documented throughout its very colorful history. While the regular renovations have obscured much of the original structure, they also reveal how much the ancient city influenced subsequent eras.

Hadrian spent years touring his vast empire, including the Egyptian pyramids as well as the necropolis cities in Asia Minor. The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World) and had already inspired the Mausoleum of Augustus just across the Tiber River. Hadrian’s version combined them into a massive drum resting on a square base, topped by a circular colonnaded temple within a ring of cypress trees. The imperial family’s funerary urns were kept deep within the structure, accessed via a spiral ramp which would later inspire architects like Bramante and Borromini.

As the Empire faltered, the mausoleum morphed into a fortress: locals hurled statues and chunks of marble down onto invaders. After an eventful thousand years, the structure came full circle when Renaissance artists painted the new Papal palace in the style of ancient Roman frescoes. See the website for visiting information.

Roman Baths, Theaters, and Arenas

Baths of Caracalla

The imperial government provided increasingly enormous leisure complexes for the general public. Besides bathing, they functioned as places to exercise, socialize, learn and find entertainment. These mega-centers pushed engineers to innovate; many hallmarks of Roman architecture like monumental vaults and domes were first developed in baths.

Inaugurated in 216 CE, the Baths of Caracalla set a new standard. Millions of bricks and many, many tons of marble plus other materials comprised the complex sprawling below the Caelian hill. Even after heavy earthquake damage and centuries of use as a quarry, its remains are still gargantuan. Vast stretches of mosaic flooring showcase the Roman dexterity in tile: in some places a distinctive leaf-checkerboard pattern appears to move.

Besides bathing facilities, the complex included indoor and outdoor exercise areas, a stadium, gardens, and terraces for sunbathing. There was also a pair of libraries, spaces for performances and readings, shops and food stalls, as well as a large subterranean temple to Mithras. The baths themselves were laid out to maximize solar power, with the seven-pool caldarium (hot room) in the southwest and four-pool frigidarium (cold room) in the northeast. Bronze mirrors reflected sunlight onto the Olympic-sized outdoor pool. The entire bathing facility was raised on a platform over furnaces which burned an estimated 10 tons of wood per day.

Baths of Diocletian

The Baths of Diocletian gives a sense of the tremendous scale Romans built on. Constructed between 298 and 306 CE, these were Rome’s largest imperial baths. At this time, cold baths were especially popular – possibly because the depletion of local forests made heating more of a challenge.

During the Renaissance, Michelangelo transformed the ancient Baths of Diocletian into a church. Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri (St. Mary of the Angels and the Martyrs) occupies only a portion of the gargantuan complex’s footprint, but feels equally monumental. The renovation preserves the original sequence of spaces: visitors enter through the remains of the caldarium, then pass through a domed vestibule (the former tepidarium) to access the main church (in the old frigidarium) from the side. Bright colors evoke the original decor.

Spaces from the bath complex in Michelangelo’s Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri church (left) and the National Museum of Rome (right).

Around the corner from the Piazza della Repubblica and across from the train station, another part of the complex houses one of the city’s most underrated venues: the National Museum of Rome. Its collection includes many of the baths’ decorative elements from mosaics to sculptures and friezes. For more information, see our post on Roman domes.

Theater of Marcellus

Conservative early Romans considered dramatic performances frivolous, and the city remained devoid of permanent theaters for centuries. The outsized personalities of the late Republic brought a major change of attitude. Pompey’s legendary, ultra-extravagant construction is no more, but the smaller version planned by his rival Caesar survives. Augustus named the theater after a favorite nephew when he finished it around 17 BCE.

The Teatro di Marcello modified the typical Greek theater. Instead of using an existing hill for tiered seating and a framed view of the landscape as a backdrop, it is freestanding and fully enclosed. Different sources cite a diameter of either 111 or 130 meters (roughly 400 feet), while estimates of its capacity range up to 20,000 spectators. The theater is the earliest dated structure in Rome to incorporate fired bricks into the established concrete-and-tufa system.

Like so many other ancient ruins, this one was used as a quarry and shelter in later centuries. Rather more unusually, it got a palazzo added on top during the Renaissance – and still has residents inhabiting apartments in the upper level. The interior opens for classical music concerts in the summertime.

Colosseum

No other building symbolizes ancient Rome like the Colosseum. Funded with loot from Jerusalem’s Jewish Temple and constructed largely by prisoners of war and slaves, it was a gift from Emperor Vespasian to the public. Distinct seating levels reinforced the social hierarchy, from emperors in a special box right on the edge of the action to the standing-room tier on top for women and slaves. Contrary to later accounts, there is no evidence that Christians were martyred in the Colosseum.

Due to earthquakes and scavengers, less than half of the original mass remains. At nearly 2,000 years old, it’s still the world’s largest free-standing amphitheater. The Colosseum plan took theaters like the Teatro di Marcello a step further, putting two semi-circles together to make a fully-enclosed oval shape. Printed pottery shard ‘tickets’ guided spectators to their seats efficiently via numbered rows, tiers, and exits (vomitoria).

Hundreds of tons’ worth of iron clamps anchored over 100,000 cubic meters (3,500,000 cubic feet) of stone without mortar. Over it all, specially-trained sailors operated a network of masts, ropes, and canvas to protect the spectators from the elements. On one memorable occasion, the awning system also enabled Emperor Domitian to literally shower everyone with food.

Circus Maximus

Very little remains of the Circus Maximus, but the sheer size of its footprint still impresses. A three-storey structure surrounded a chariot-racing track over 600 meters (2,000 feet) in length. Estimates of its full capacity range from 150,000 to 300,000 spectators, or around three times greater than the Colosseum. For perspective, just a handful of horse-racing venues built in the last 150 years can hold over 100,000 people; the biggest is Tokyo Racecourse with a capacity of 233,000. Thanks to its size, the Circus Maximus allowed a broader range of the population to mingle than any other venue – sometimes with dangerous results.

On the left, the Lateran Obelisk which one decorated the Circus Maximus. On the right, the site today, with grass mounds added by Mussolini to evoke seating tiers.

Among the treasured objects displayed along the spina (central barrier) were a pair of obelisks shipped from Egypt. Egyptian civilization was as ancient to the Romans as they are to us, so these monuments made quite a power statement. Emperor Augustus had the first of Rome’s 13 obelisks imported at enormous expense and installed in the circus; today it anchors the Piazza del Popolo. Several hundred years later, Constantius II brought over what is still the world’s largest standing obelisk, which is now in front of the Basilica of St. John Lateran.

Roman Palaces and Residences

Domus Aurea

Begun in 64 CE after a fire destroyed much of the city, Emperor Nero’s Domus Aurea (Golden House) was scandalously excessive even by ancient Roman standards. The vast estate sprawled down the Palatine Hill, across the valley, and up the Esquiline, Oppian, and Caelian Hills. Nero’s successors dissociated themselves by building over the property, for example replacing the private lake with the Colosseum. Modern excavations have revealed portions of the old palace, mostly under the Baths of Trajan. Special tours of the site include a visit to Nero’s legendary domed dining room.

Ancient descriptions of the Domus Aurea mention feasts under a rotating dome and a system of pipes for raining perfume. Today it’s an octagonal room topped by a 13-meter (43 feet) hemisphere, the earliest major dome we know of in the city. Walls radiating out from the space buttress the concrete span, lit by an unusually large oculus in the center. The opening spans nearly half the room and probably supported a cupola, which could have been the rotating part. The site’s website doesn’t always load, but the ticketing page has visiting information.

Palatine Hill and the Houses of Livia and Augustus

Tickets to the Roman Forum include access to the Palatine Hill looming above it. This is the site of the city’s first settlement as well as its most monumental residences. Ruins range from the foundations of a trio of Iron Age huts to portions of the Imperial Palace complex overlooking the city. Between these two extremes lie the House of Livia and House of Augustus, which date to the late first century BCE.

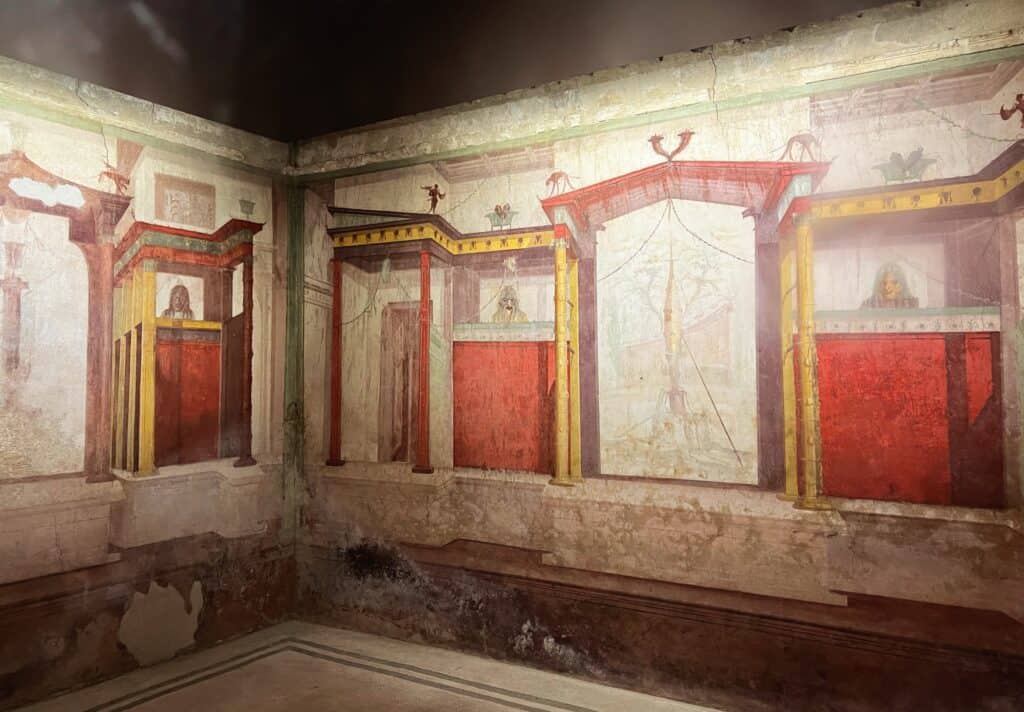

Rome’s first emperor presided from an expansive but relatively modest set of villas. These included the former home of lawyer Hortensius (rival of Cicero) which may have been occupied by Augustus’s wife Livia. Like the nearby House of Augustus, it includes courtyards – the traditional heart of Roman homes – and an assortment of rooms, not all of which have been identified. Both properties also retain the distinctive wall frescoes and floor mosaics which make Roman domestic architecture so striking and unique.

Further Reading

For more on Rome, see our posts:

A Guide to Rome’s Ancient Churches and Basilicas

Italy’s Most Stunning Mosaics from Rome to Ravenna to Sicily