A Guide to Art Nouveau Architecture in Sóller, Mallorca

Set against the stunning backdrop of the Serra de Tramuntana mountain range, the town of Sóller is a popular travel destination, both as a day trip from Palma or as a base for hiking and biking in northwestern Mallorca. As if the surrounding scenery isn’t enough, Sóller (pronounced SOY-er) also boasts a surprising amount of Art Nouveau architecture. The island’s vocabulary of honey-colored stone with green trim might not seem like the most fertile ground for architectural experimentation, but Sóller was once a hotbed of Modernisme. From the iconic Sant Bartomeu church in the central square to the Sa Capelleta shrine tucked amongst the valley’s citrus and olive groves, the range of structures makes a perfect complement to the region’s beaches and hiking trails.

Sóller and the Valley of Gold

Ancient Romans brought olives and grapes to the island, but agriculture didn’t flourish until the tenth century. When the Moors arrived, they began cultivating olive trees on a large scale; their olive oil led to the nickname “Valley of Gold.” The Moors also started growing oranges and lemons, bringing wealth to the region. After the Reconquista in 1229, the valley began a steady stream of trade with France.

Europe’s industrialization in the second half of the 19th century brought unprecedented changes to the urban environment. The Art Nouveau movement combined artisanal craftsmanship with new materials to create a dynamic style, full of whiplash curves and expanses of glass. In Barcelona, architects like Antoni Gaudí created a local variation on Art Nouveau by combining it with regional building techniques; their work came to be known as Modernisme in Catalan and Modernista in Spanish.

In 1912 a new railway through the mountains gave Sóller and the valley a direct connection to Palma and the outside world. Anxious to demonstrate their sophistication, Sóller’s wealthier residents commissioned structures to rival those of Palma, Barcelona, and France.

Central Sóller

The Church of Sant Bartomeu and the Banco de Sóller

When Gaudí traveled to Palma to renovate the cathedral, he brought along his protege Joan Rubiò i Bellver. Rubiò in turn came to Sóller, creating new façades for its main church and the prominent bank on the Plaça Constitució. Because he worked on the two at the same time (roughly 1912-14), he was able to play the buildings off of one another – and to transform the town’s main square in one stroke.

Rubiò’s design for Sant Bartomeu resuscitated the structure’s Gothic origins. (The 13th century church had been rebuilt in a Baroque style after it collapsed in 1688.) It follows the tradition of a grand central portal under a rose window, capped by a pair of towers on either side. The twist comes at the top, where a series of vertical openings give a feeling of lightness. The alternation between stone and the landscape beyond integrates the structure with its magnificent surroundings.

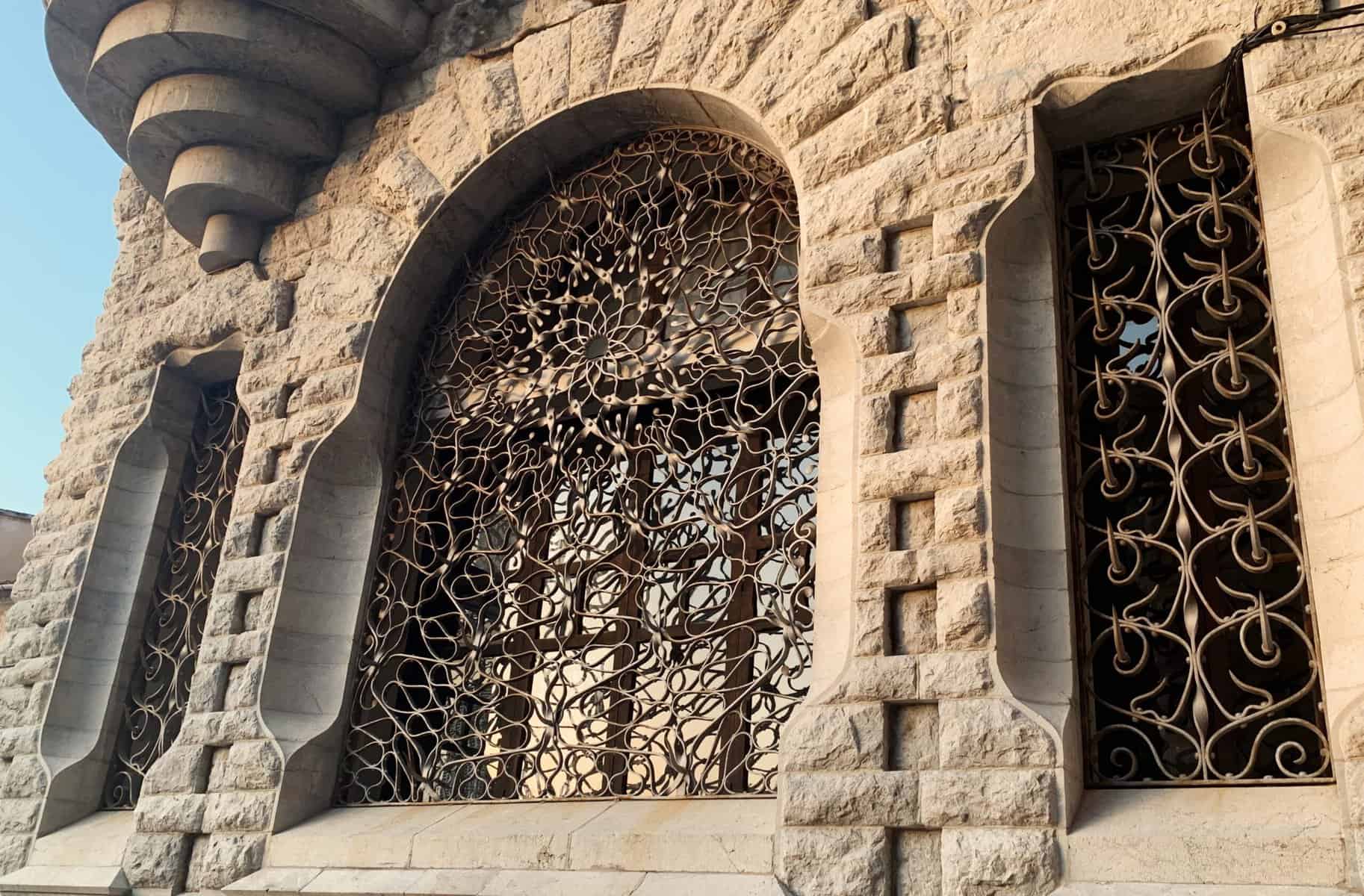

The bank also starts from a traditional form, in this case the austere financial palaces of Renaissance Florence. Rubiò balanced this severity with the playfulness of Catalan Modernisme.

He carved into the corner to make an oddly-shaped opening with not one but two semicircular stepped balconies underneath. Then he cut sinuous, irregular curves around the windows, and added wild spider-web window grilles.

Can Prunera

Sóller’s main shopping street, the Carrer de sa Lluna, holds several Modernista buildings. The best is Can Prunera, built between 1904-11 to showcase a local family’s fortune. Rumors of Rubiò’s involvement in the design have never been proved, and the architect remains anonymous.

Art Nouveau design promoted a “total environment” which blurred the boundaries between art, architecture, and everyday objects. The Can Prunera’s collection of artwork, furniture, and textiles blends seamlessly with its array of tiles, etched and stained glass, ironwork, woodwork, sculpted and painted accents, and light fixtures.

Admission includes access to a museum area with pieces by early 20th century masters (Miró, Toulouse-Lautrec, Klee, Léger) as well as local artists.

Gran Hotel Sóller

Pick up a citrus gelato from the justly-famous Gelat Sóller, and continue down Avinguda de Cristòfol Colom for about a block to the Gran Hotel Sóller. The 1880 structure began as a mansion but added a leather and tanning factory in the rear, producing boots during World War I. When tourism took off on the island, it was converted to a 5-star hotel.

Around Sóller

Sóller Cemetery

Some of the best views of the mountains and valley can be found from the terraces of Sóller’s cemetery. Situated on the outskirts of town, it’s an atmospheric sunset walk. We went to see the Modernisme fixtures and carvings and were taken by the reverence we found everywhere.

Sa Capelleta Santa Maria de l’Olivar Sanctuary

Between the views of the Serra de Tramuntana and the lush vegetation, it’s impossible not to be transfixed by the landscape along the trails surrounding Sóller. The Modernista sanctuary, along the route to Fornalutx, comes as a surprise.

Raw stone walls seem to grow from the mountain, eventually coalescing into the grounds of a garden. A tiny church built along fairy-tale lines turns out to hold a shrine, circa 1917.

If we hadn’t noticed a modern sign on the edge of the complex, I might have wondered if we hadn’t entered another world.

Visiting Sóller

Sóller Train & Train Station

Pictures of Sóller inevitably feature its vintage trains and trams, still in operation after over a century. This is Spain’s last surviving rail system from the early 20th century. It was also the most direct form of transportation outside the valley until the 1997 vehicular tunnel opened. Only after experiencing its serpentine mountain roads did we fully understand how isolated Sóller was before the train.

The trains run to Palma, while the trams go to the nearby beach enclave of Port de Sóller. Although pricier than the modern bus system, the scenery is better – and the wooden railcars are hard to resist. See the website for information on routes, schedules, and prices.

The train station in Sóller occupies the 1606 Can Mayol, and is an attraction all by itself. As an added bonus, it also holds a collection of ceramics by Picasso and engravings by Mirò which can be visited for free. (Mirò’s grandmother was from Sóller, and he donated the works in the 1970’s.)

accommodations

We adored our hotel, the S’Ardeviu. The garden makes a quiet refuge from the bustle of town, while the building has been beautifully restored. Owners Isabel and Xisco serve fresh orange juice and breakfast in the garden. Their citrus preserves are easily the best we’ve ever tasted.

more information

All of the sites above are included on our Google map.

We also have posts on Modernisme in Palma de Mallorca and the medieval architecture of Palma’s Old Town.