History of the Alhambra’s Paradisal Gardens and Courtyards

Inspired by paradise itself, Granada’s Alhambra holds the power to transport us from the cares of the outside world. In spite of being photographed thousands of times per hour every day, the palace still generates a feeling of enchantment which cannot be replicated. Its gardens and courtyards form an all-encompassing sensory experience where indoor and outdoor spaces blend, and the earthly becomes heavenly.

Legends about the Alhambra are easier to find than facts. No one can provide a definitive guide for such a complicated site. A surprising amount of information about it – even from normally reliable sources – is conjecture or inaccurate. Part of the Alhambra’s mystery comes from its layered history; what we see today is largely a restoration, but the original design was itself an evocation of a lost garden paradise.

Orientation

Many consider the Alhambra to be the third and final great Islamic site of medieval Spain after Córdoba’s Mezquita and Seville’s Alcázar. The complex built by the Nasrid dynasty was once a city with up to 40,000 residents sprawling across the Sabika Hill.

At the slope’s lower end, overlooking the city, the Alcazaba fort incorporates the oldest structures on the site. Today, visitors enter near the middle section, which encompasses the main Nasrid-era structures as well as the Charles V Palace and museum. The Nasrid Palaces contain a series of spaces – some public, some private – occupied by the royal family and their retainers. Across a ravine, the Generalife Gardens served as the king’s personal retreat, while the wilder tracts beyond hosted hunts and other outdoor activities.

Before the Nasrids

Gardens as Paradise

The story of the Alhambra begins in the Middle East, with the origins of the “paradise garden.” In the hot, dry climate of the region, gardens – and water – have been revered as the source of life and a reflection of the divine. Humans began creating walled gardens about 12,000 years ago. Written and pictorial descriptions go back to the most ancient civilizations, including the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. In Mesopotamia, growing cities led to canals, urban gardens, and palaces with courtyard gardens. Legends arose: the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Assryian Garden of Delights, and the Biblical Garden of Eden. Eventually the Greek traveler Xenophon translated the Persian word for walled garden, pairidaeza, to paradeisos, or “paradise”.

By the time of Cyrus the Great (590-530 BCE), Persians had created the foundations of the garden tradition used in the Alhambra. Along with advancing technology, such as building underground conduits of up to 80 km to carry water, they formalized the famous four-part garden plan. The chahār-bāgh layout consists of a square divided into four equal parts by a pair of intersecting walkways or water courses.

The Escalera del Agua, or Water Stairway

Muslim texts describe heaven as a series of gardens, with frequent mentions of water and various plants in the Qur’an. Water represents purity, cleansing and refreshment; plants with religious significance include the myrtle, palm, cypress, olive, fig, pomegranate, and grape. Some say that the four-part garden symbolizes the four rivers of paradise, which flow with milk, honey, wine, and water. The symmetrical layout introduces the idea of repetition, used extensively in Islamic architecture.

Paradise gardens often incorporated plants for consumption and medicine as well as some ornamental accents. Of these, the most iconic might be citrus and other fruiting trees, lavender, roses, violets, and lilies.

The Qur’an calls water the basis of creation, and it plays a central role in Islamic gardens. The Alhambra gardens feature it everywhere, in myriad forms. Sparkling droplets flying through the air make a focal point, while transparent streams provide a quiet accent. Sometimes, in still pools, it almost disappears behind a reflection of the surroundings. Water also provides a soundscape by swishing along a channel, burbling from a fountain, spraying from a jet, or silently filling a basin. It can even carry a scent, such as when the sprinklers run amongst the shaded paths in the morning.

Garden Revolution

The land around Granada has held gardens for as long as there are records of human settlement. While other parts of Spain offered lucrative mining opportunities, the Romans arriving in the second century B.C.E. recognized that Granada’s wealth lay in the fertile plain at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains. The Romans began water management by tapping springs and building cisterns to collect water. But it was the Arabs and Berbers arriving in the eighth century who would make the Alhambra possible.

Just as Romans changed the world with their engineering genius, Islamic culture changed it with a gift for horticulture. The Iberian Peninsula in the Middle Ages witnessed revolutions in water and land management, an influx of new plants imported from across the Mediterranean, and systematic studies of propagation. Large-scale development on the Sabika Hill required an innovative system of waterwheels, pumps, and conduits to bring water up to the site.

Under the Nasrids

The Nasrids ruled the Kingdom of Granada from 1232-1492. As the last Muslim dynasty in Spain, they occupied a precarious position between the external Christian threat and internal power struggles. Seven of the first nine kings were assassinated, while many later kings were ousted at least once. (Muhammed IX managed four distinct reigns.) The tumultuous politics forced the Alhambra complex to grow piecemeal without an overall plan. Eventually the site would feature something like six individual palaces, well suited to housing the many competing factions.

As Christians gradually took control of the Iberian Peninsula, Granada became a repository for Muslim culture. Yet even as the city flourished, its residents would have been aware that it might not survive. The Nasrid kings opted to build in materials like stucco and tile rather than marble and bronze in order to increase the speed of construction.

The buildings now connected were originally separate structures, surrounded by roads and buildings which no longer exist. Most of the current names came into use after the Nasrid period and don’t indicate how the space might have functioned. For instance, the Sala de Dos Hermanas, the Hall of the Two Sisters, is named after a pair of stone slabs, while the ‘Palace of the Lions’ may actually have been a madrasa, or religious college. To complicate things further, many of the buildings probably served different purposes at different times. Traditional Islamic architecture tends not to assign fixed functions to each room, relying instead on portable furnishings to define a space.

Many of the gardens would have felt like outdoor rooms. Most of the planting beds were submerged, leaving a relatively flat surface – almost a carpet of greenery. Textiles and screens would have been added to create shade, and cushions would turn the space into a lounge.

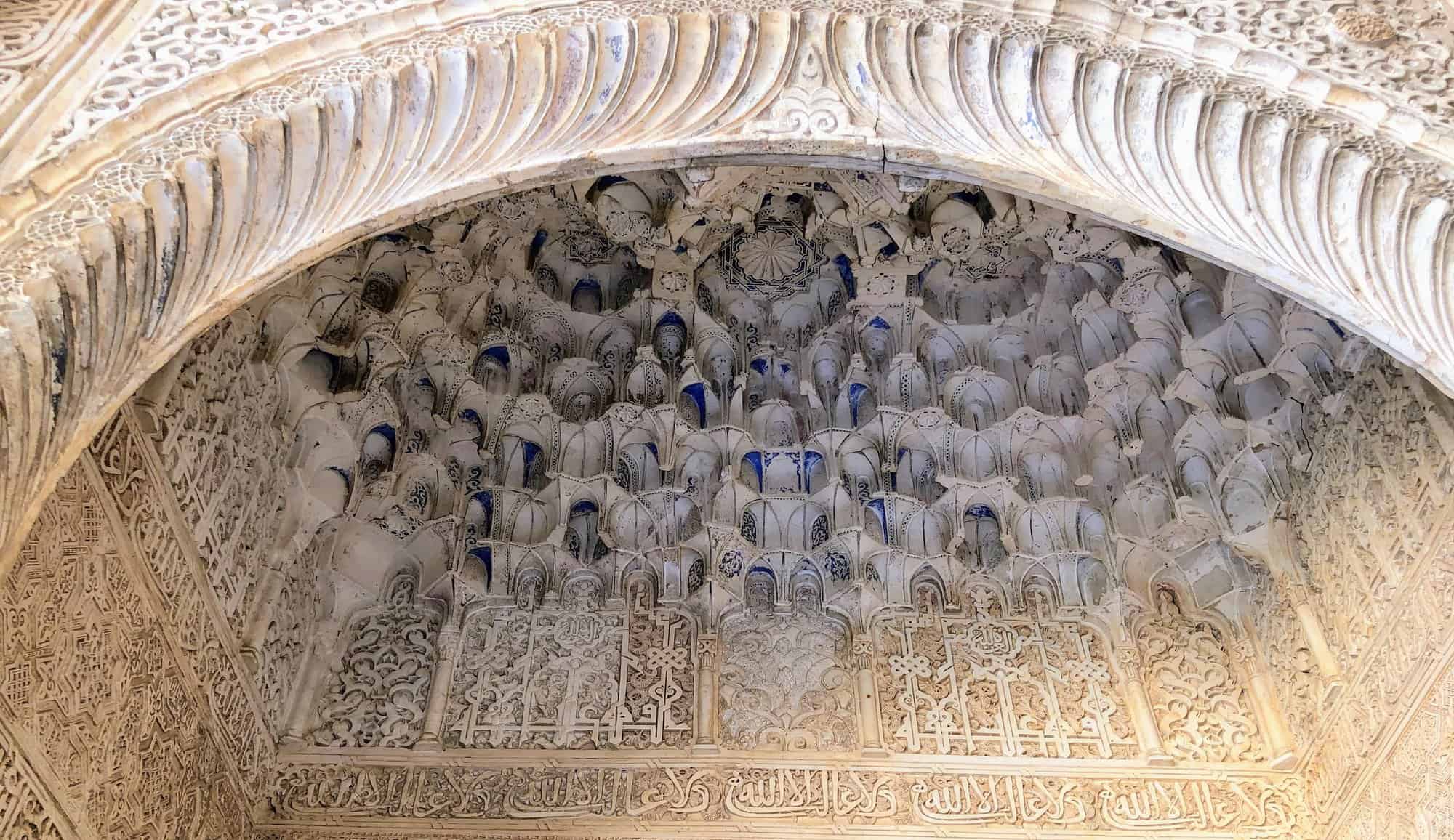

Meanwhile, the rooms extended the courtyard space. Besides being defined by rows of columns instead of solid walls, they featured the same materials and decorative accents, even extending channels of water to the interior. Some of the ornamentation deliberately evokes the natural world, perhaps most spectacularly in the intricate muqarnas.

The standard description of muqarnas as ‘stalactite vaulting’ hints at its appearance, which can evoke a cave. This ties in to the significance of caves in Muslim texts and many forms of mysticism. The poetry on the walls hints at another interpretation, however. In the Hall of the Two Sisters, Ibn Zamrak’s verse likens the muqarnas dome to the starry sky. Only traces of paint remain today, but we can picture the Nasrid colors of blue and gold turning the stucco into a heavenly dome, especially by candlelight.

The enigmatic Courtyard of the Lions continues to inspire artists and puzzle scholars today. The lions themselves have generated countless legends and theories, particularly since Islamic art normally avoids representations of animals. It’s not clear if their abstract style made them less provocative than the paintings of men on the ceiling of the Hall of the Kings, but the poem on the basin refers to them as a metaphor for the king’s war power. Another pair of lions, probably by the same sculptor, once sat at the Albaicín quarter’s Maristan hospital.

After the Nasrids

While much of the Alhambra did not survive, the complex could have fared worse. Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella carried out some repairs after assuming control of Granada in 1492. Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was also taken with the site, although he felt it necessary to add his own discordant palace. Eventually Granada’s prominence waned and so did interest in the Alhambra.

The Spanish began using the parts of the Alhambra as a prison in the 17th century. Later it housed invalid soldiers, itinerant Romany clans, random travelers, and even livestock. Earthquakes and fires caused further damage, but the worst calamity was the occupation by French troops in the Napoleonic wars. The general’s fascination with Eastern cultures inaugurated a European craze which cast the Alhambra as an exotic “Oriental” monument. Unfortunately this led to a stream of visitors who plundered the site and chipped carvings from the wall as souvenirs.

Restorations

By 1870, the accounts of Washington Irving and others had raised the Alhambra’s profile enough for it to be declared a national monument. But because of the lack of documentation, restoration has been challenging. In spite of the sophisticated mathematics required for the decorations, structures were not planned out on paper. Consequently, our only contemporary sources for what the site might have looked like in its heyday comes from written descriptions, mostly from foreign visitors.

Soil analyses have yielded information about the presence of specific plants, but the layout of the gardens is even more of a mystery than the buildings. Most of them were ‘restored’ about a century ago, with copious use of Italian-style boxwood hedges and other anachronisms.

On a broader level, the Alhambra today presents a good approximation of the land’s condition in the Nasrid era, with plots dedicated to agriculture (huertas) and swathes of wilderness at the upper end. In some cases, the restoration includes an inspired marriage of landscaping with archaeology. For instance, the Patio de Machuca features a wall of cypress planted where a stone wall once stood.

Planning a Visit

Alhambra tickets sell out early, so it’s vital to reserve several months in advance on the Alhambra-Generalife website. Note that visitors need to bring a passport or identity card on the day of the visit.

Although the ticket possibilities can be overwhelming at first, they all offer variations on the same three areas. We recommend the “Dobla de Oro” ticket, which includes access to the Andalusian Monuments covered in our post on the Albaicín quarter.

Further Reading

Washington Irving’s Tales from the Alhambra is the classic source for legends.

At the other extreme, Robert Irwin’s book The Alhambra presents a concise overview of what we do – and don’t – know about the site.

We also have posts on Spain’s Islamic architecture, Córdoba’s Mezquita, Islamic architecture in Seville, and Toledo’s Mudéjar architecture.