The History of Sainte-Chapelle: Paris’s Stained Glass Temple

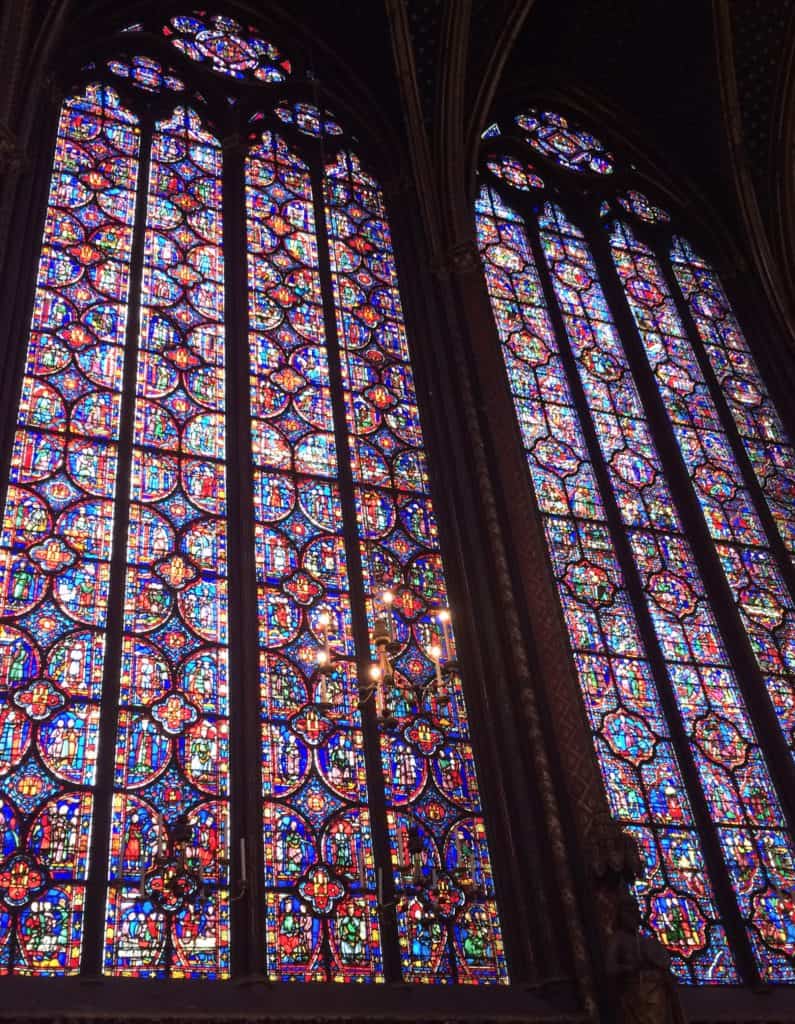

Stepping into Paris’s Sainte-Chapelle is like entering a jewel. The upper level has almost no walls, just swathes of light in myriad colors washing through the lofty space. It’s the pinnacle of a style which began in the Basilica of Saint-Denis just over a century earlier. If you can tear your eyes away from the glowing panels – and you may not be able to – notice the expressions on the people around you. It’s not the biggest or the most famous of the city’s churches, but you won’t find anything more jaw-droppingly beautiful.

Traditionally, we’re told, modernity began in the Renaissance – and yet Gothic cathedrals present us with daring structures erected by a society in the midst of staggering change. For the first time in history, walls didn’t need to block out the world or hold up a roof. Slender columns and intricate vaults did the work instead, rising up to unprecedented heights while supporting delicate membranes of colored glass.

Western Europe’s Emergence from the Dark Ages

The invention of a few humble agricultural tools enabled Europe to begin emerging from the Dark Ages. Fewer people produced more food, and the population dramatically increased: from roughly 40 million in 1000 to 75 million in 1300. More people meant society could grow beyond the old knight-clergy-serf model; a skilled labor force developed and, along with it, trade. People began to congregate in cities, with a building boom in urban structures – most notably, the cathedral.

At the same time, Western Europe’s contact with the rest of the world increased, bringing back not only classical knowledge lost in the Dark Ages but also advances from the Muslim world. In the eastern Mediterranean, traders and Crusaders discovered innovative buildings with an entirely new vocabulary of forms. Soon Islamic pointed arches and ribbed vaulting began to appear on European soil: the former spreading from Muslim Spain to southern France and the latter brought back by crusading Normans.

In the small territory known as the “Île-de-France” masons began experimenting with these new techniques. These experiments, combined with the religious and political agenda of France’s monarchy, gave birth to the style known today as “Gothic.”

From Early Gothic to the Rayonnant

In the middle of the 12th century, renovations at Saint-Denis pioneered the use of columns and vaulting for the entire structural load, freeing up walls to be replaced with panels of stained glass. Other churches adopted Saint-Denis as a model. Because cathedral construction was booming at the time, the new style quickly blossomed. Master stonemasons evolved into architects, some of whom we know by name today, such as Notre Dame’s Pierre de Montreuil, the “doctor of stone.” They began using drawings to experiment and plan projects out ahead of time. Drawings also allowed for faster exchanges of ideas.

As if dematerializing the wall wasn’t radical enough, Gothic structures also abandoned arcades. Instead of using tiers of arches, the new cathedrals ran columns straight up to ever-higher vaulting. They reached to the heavens with no regard for human scale.

The glass windows told stories – handy for a population with a low literacy rate – within panels of various shapes. Most of these would follow the general design of the structure, but the ultra-symbolic rose window soon came to predominate. Because its form mimicked the sun and the source of light itself, the circular window inspired the name “Rayonnant.”

Sainte-Chapelle

In 1238, desperate financial and political circumstances prompted the Byzantine emperor to offer some coveted relics to Louis IX, the king of France. In spite of their astronomical price, “Saint Louis” was only too eager: what symbol could be more resonant to a monarch than the legendary Crown of Thorns worn by Jesus himself?

Essentially a shrine for the Crown of Thorns, Sainte-Chapelle was built in record time (a mere six years) and at enormous expense (still less than a third the cost of the relics themselves). And it set a new standard for Gothic architecture.

Tucked into the palace complex on the Île de la Cite, the exterior is majestic but not overwhelming. Unlike cathedrals such as Notre Dame, this relatively small structure doesn’t require flying buttresses or other hallmarks of monumental Gothic architecture. Considering that Sainte-Chapelle was primarily a private royal chapel, however, the scale is impressive. A lower level holds a chapel for the non-royal residents of the island with a complex series of arches unified by its painting scheme.

Sainte-Chapelle’s upper level embodies “sacred space.” Interior surfaces painted in deep blue, red, and gold echo the jewel tones of the windows and turn the entire chapel into a three-dimensional tapestry. Apparently most Gothic churches were painted, but restorations have tended to leave the stone bare. The design avoids ornate flourishes which were common at the time; some scholars call it “classical Gothic.” Many visitors say it feels modern.

The legacy of Sainte-Chapelle

Sainte-Chapelle would be copied for centuries all over the continent – except in France itself, where no one wanted to compete with its perfection.

It even came through the French Revolution without too much damage, in spite of its significance as a symbol of the Ancien Régime. Naturally, rebels looted the valuable reliquaries, but they left nearly all the stained glass intact. (Unlike the Basilica of Saint-Denis, which lost its windows and roof.) Perhaps the rioters already planned to use Sainte-Chapelle as a granary, and preserved the windows to keep the interior dry. But I’d like to imagine that the power of the space might have restrained them.

Practicalities

Sainte-Chapelle sits in the very center of the city, in the the Palais de la Cité (the old royal residence) on the Île de la Cité. The Notre Dame is an easy five minute walk.

Purchase tickets online through the Paris tourist office. Admission is free with the Paris Pass.