Castello: Venice’s Sestiere of Secrets

For most of its existence, Venice has been synonymous with secrecy, and no district embodies this better than Castello. Mysteries, illusions, and historic trickeries abound in the city’s easternmost district, from Viking runes carved on an ancient Greek lion statue to a Renaissance façade hiding a modern hospital. Named after a fortress lost to the centuries, Castello offers tantalizing glimpses of a past littered with secrets.

Orientation

Castello is the only one of Venice’s six sestieri (districts) which doesn’t touch the Grand Canal. It juts out from Cannaregio and San Marco, bounded primarily by the waters of the lagoon. Because of its large size and relative remoteness, the district gets less tourist traffic, especially past the Arsenale. Castello’s southern edge forms one of the world’s most scenic waterfronts, backed by a string of eclectic churches. The massive Arsenale, Venice’s legendary shipyard, runs down the middle of the sestiere, effectively dividing it in two. Most of the historic sites cluster closer to San Marco, with the neighborhood becoming quieter and more residential further out.

Castello’s eastern end contains a mixture of residential and industrial areas, along with Napoleon’s public gardens. Pavilions transform much of the area during the Biennale exhibitions, which alternates between art and architecture each year. The shopping street of Via Garibaldi runs from the waterfront promenade to the island of San Pietro di Castello. Both the latter and the larger island of Sant’Elena connect to the rest of Castello with footbridges.

All sites are marked on our Google map.

Riva degli Schiavoni

Arsenale & Lions including Porta Magna and Museum of Naval History

Parish Churches: San Zaccaria, San Giovanni Battistà in Bragora, San Martino di Castello

Scuola and Church of San Giorgio dei Greci

Campo Santa Maria Formosa: Church of Santa Maria Formosa, Palazzo Grimani, Querini Stampalia Palace

Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo: Santi Giovanni e Paolo (San Zanipolo), Scuola Grande di San Marco, Colleoni Monument

Palladio Church Façades: San Francesco della Vigna, San Pietro di Castello

Practicalities: Staying in Castello, Transportation

Further Reading

Riva degli Schiavoni

A waterfront promenade beginning at the Palazzo Ducale continues all the way to the island of Sant’Elena, a walk of about 25 minutes. The most famous – and crowded – stretch is the Riva degli Schiavoni, between the Doge’s Palace and the Arsenale. With unbeatable views of St. Mark’s Basin, this area also gets traffic from Castello’s biggest vaporetto hub.

Arsenale & Lions

As an empire based on maritime trade, Venice’s ships were its lifeblood. In 1104, the massive Arsenale was established as the primary site for building ships. High walls protected trade secrets and helped contain the hubbub. Inside, the world’s first large-scale assembly-line production churned out up to 50 warships per month, employing as many as 16,000 workers. Its fame spread so far that Dante mentioned its pits of boiling pitch in the Inferno. Galileo became a consultant here in 1593.

Crenellated walls and towers make the Arsenale feel like a castle. Since much of it remains closed to the public, the place still retains an aura of mystery. The Italian Navy and the MOSE barrier project offices use most of the site, with certain portions opening during the Biennale. A historic entrance on the southern end known as the Porta Magna pays tribute to the city’s pride in the Arsenale with an early-Renaissance gateway and ancient lion statues.

Venice has a higher concentration of lions than just about anywhere, so it’s no small thing when we say that the sculptures outside the Arsenale are our favorites. Francesco Morosini looted them when the Venetians captured Athens in 1687, accidentally blowing up part of the Parthenon in the process. Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that three of the four lions here lost their heads at some point.

The Porta Magna also features a pediment with the classic Lion of St. Mark. This one, however, is a rare example with a closed book instead of an open one, symbolizing the city at war.

On the gate’s left sits the most famous and intact of the lot: the Piraeus Lion, which once guarded the port in Athens. At over nine feet tall, the 2,400 year-old statue has mysterious 11th-century Viking runes carved into its flank.

Across the gateway reclines the Hephaisteion Lion, whose gentle smile belies the local legend about its murderous exploits. Further to the right is the Lion of Delos, an inexplicable amalgam: the elongated body is one of about a dozen from the fourth or fifth century BCE found outside the Temple of Delos, while the 17th century head could have inspired the Pink Panther. Next to the canal, the smallest lion – with an undersized replacement head – remains unattributed.

Venetians planned out their ships with elaborate large-scale models, many of which are on display at the Museum of Naval History. Most visitors can focus on the vessels in the Padiglione delle Navi (Ships Pavilion) below the Arsenale, but history and maritime enthusiasts could easily spend a sizable chunk of the day in the sprawling complex.

Parish Churches

A large number of refugees arrived in Venice around the year 650, fleeing invasions. According to legend, San Magno founded no fewer than eight churches in the vicinity around this time. Funded and controlled by local residents, these smaller churches are inextricably linked with neighborhood histories.

San Zaccaria

Historical records for the church begin in 828. The current façade shows Venice transitioning into Renaissance architecture. An older interior includes a permanently-flooded and highly atmospheric crypt with the tombs of eight early doges. Paintings include work by the three T’s (Titian, Tintoretto, and Tiepolo) and a Van Dyck. Pride of place goes to Bellini’s Madonna, perhaps his finest altarpiece. Like many works of the era, the painting echoes the architecture around it to create an illusion of depth.

San Giovanni Battistà in Bragora

Allegedly founded in the seventh century and first documented in 1090, the current Church of San Giovanni in Bragora dates to 1475. Although Gothic in style, the façade’s austerity matches early Renaissance structures in Florence. Inside, a rare ship’s-keel ceiling arches over a collection of ancient columns looted from the eastern Mediterranean. A plaque notes Vivaldi’s baptism here; fans of the composer can also visit the nearby Santa Maria della Visitazione (a.k.a. la Pietà) where he worked for many years.

San Martino di Castello

Dating to at least 932, the Church of San Martino di Castello once ministered to the neighborhood’s dock workers. Although they managed to obtain a design from the famed Jacopo Sansovino – architect of the Library and Loggetta on St. Mark’s Piazza – the poverty of the parish extended construction of the interior to nearly 80 years.

A façade added in 1897 retains the Renaissance doorway and one of the old bocca di leone, “lion’s mouth” boxes where Venetians could report misdeeds to the government anonymously.

Scuola and Church of San Giorgio dei Greci

Venetian trading connections made Castello a natural base for immigrants, and the district hosted communities from the Balkan Peninsula and Greece. The former group, referred to as Schiavoni (Slavs), inspired the waterfront’s name. They eventually organized one of the city’s major charitable organizations, the Scuola Grande di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, housed in a building painted by Carpaccio.

Refugees from Byzantium poured into Venice after the Ottoman conquest in 1453. The Greek population swelled, exceeded in size only by the Jews. In 1526, the city granted permission to practice Eastern Orthodox worship, and soon after the community erected the church of San Giorgio dei Greci. The Renaissance-style interior holds an elaborate golden iconostasis (icon screen).

Campo Santa Maria Formosa

One of Venice’s largest and most scenic squares, the Campo Santa Maria Formosa features a nearly free-standing church surrounded by a series of historic palaces.

On the base of Santa Maria Formosa’s bell tower, a famous grotesque with facial growths evokes the plague. Venice’s density made it particularly vulnerable to epidemics, prompting the world’s first quarantine regulations. The term “quarantine” refers to quaranta (40), the number of days in a standard isolation period.

Church of Santa Maria Formosa

Formosa translates to “buxom”, which is apparently the form assumed by the Virgin Mary when she appeared to St. Magnus and instructed him to build a church in her honor. Early records date to 1060, and the original church’s dimensions were preserved through multiple rebuilds.

Early-Renaissance architect Mauro Codussi brilliantly fused Byzantine and Latin traditions in his floorplan; unfortunately his designs for the exterior were lost after his death midway through construction.

Palazzo Grimani

After several decades of restoration, the Palazzo Grimani opened as a museum in 2008, and it is a wow. The powerful Grimani family began their collection of ancient art with pieces found on their land on Rome’s Quirinale Hill. Later, they donated the lot to the Venetian government under the condition that everything be displayed to the public – not exactly common practice in 1587.

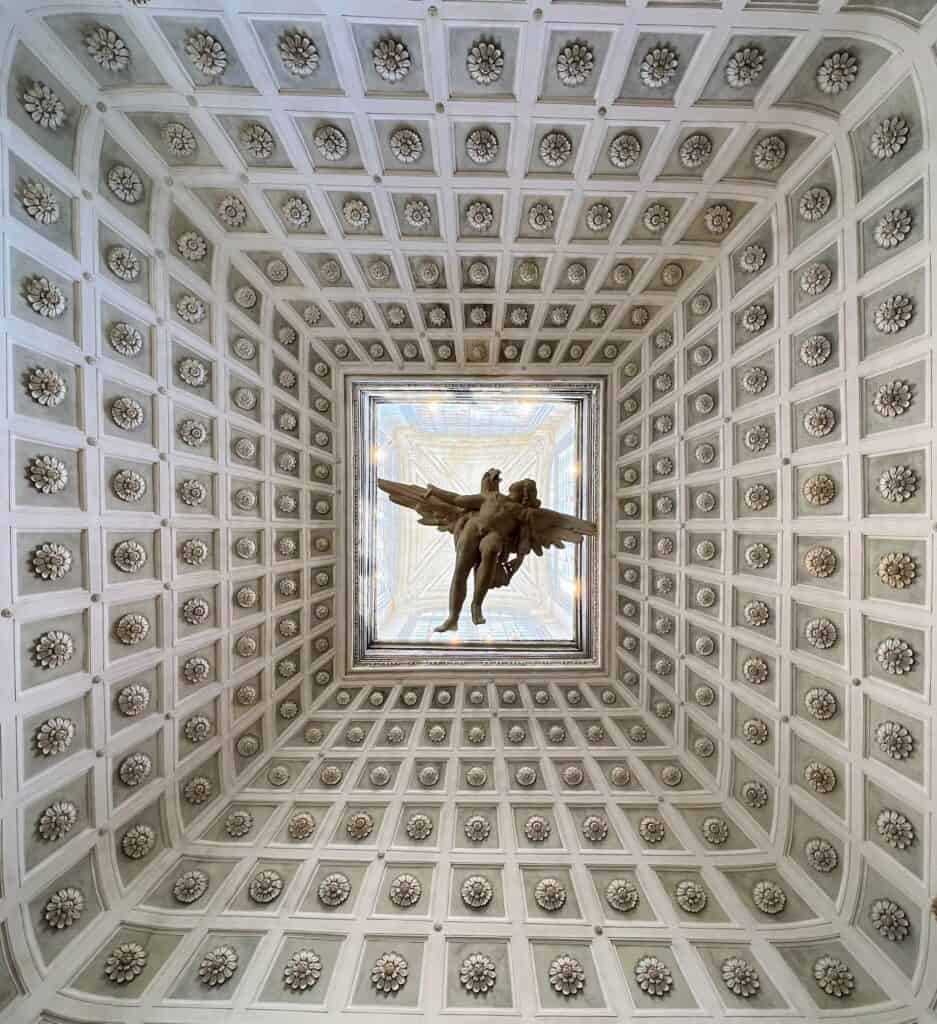

For centuries, the statues formed the core of the Museum of Archaeology, while the Palazzo Grimani moldered. After a major restoration, some works have been brought back for display on a rotating basis. The building features several inventive takes on Classical Roman architecture, most notably in the spectacular Tribuna.

The palazzo’s show-stopper staircase rivals those in the Doge’s Palace and Marciana Library, but the space to linger in is the Sala a Fogliami (“Foliage Room”). Medieval ceiling frescoes of flora and fauna seem to spring out from the vaulting in a tangle of greenery and wings.

The combined ticket for the Palazzo Grimani and the Ca’ d’Oro in Cannaregio is one of Venice’s highlights.

Querini Stampalia Palace

The Fondazione Querini Stampalia showcases the Querini family’s art collection in its original setting, including works by Bellini, Longhi, Tintoretto, Tiepolo, and Canaletto. We especially appreciated the section devoted to scenes of Venetian life over the years. A handful of modern architects such as Carlo Scarpa and Mario Botta remodeled some parts of the palace, and the foundation displays some contemporary art as well.

Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo

Although this square is one of the busier places in Castello, it still feels surprisingly quiet given its proximity to the Rialto Bridge.

Santi Giovanni e Paolo (San Zanipolo)

Rivalled only by the Frari church for Gothic grandeur, the Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo (or Zanipolo) combines uniquely Venetian architecture, art, and history. On the exterior, a late-Gothic portal incorporates columns salvaged from the ancient settlement on Torcello island.

Inside, gentle light from the rare original stained-glass windows softens the contrast between the raw brick walls and white stone accents. From the 15th century on, this was the site of ducal funerals and burials, and 25 doge’s tombs make it the largest group anywhere.

Scuola Grande di San Marco

The Renaissance facade of the Scuola Grande di San Marco has more ornamentation than the Gothic church next door. Several architects worked on project, resulting in a quirky mixture of Byzantine, Venetian, and Renaissance elements. Both elegant and extravagant, this beloved façade quickly became famous. The lower portion includes a series of reliefs showcasing the period’s fascination with perspective.

Most of the structure’s artwork was moved elsewhere, and the building eventually became the city’s main hospital. Today it houses a medical museum, with more modern hospital facilities behind it. Venetians created a government-sponsored health care system centuries before the rest of Europe.

Colleoni Monument

Further down the piazza stands Verrochio’s statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni. The mercenary promised to donate his fortune to Venice if the city erected a monument in his honor in front of the ‘San Marco’ – meaning the basilica. Knowing the nobility would never accept such a prominent location, the crafty Senators accepted the money and installed the statue in front of the Scuola Grande di San Marco instead.

Palladio Church Façades

San Francesco della Vigna

On the less-travelled northern edge of Castello lies the former monastery of San Francesco della Vigna. According to legend, an angel visited Saint Mark on this spot, predicting the rise of a city honoring him. In 1253 Franciscans replaced the chapel here with a church, naming it after the surrounding vineyard (vigna).

A reconstruction begun in 1534 used a design by Jacopo Sansovino with modifications by the prior. The outsized scale of Andrea Palladio’s 1568 façade is a surprise on such a compressed site. His groundbreaking design used different scales to distinguish their layers and similar shapes to unite them.

Besides work by Veronese and Tiepolo, the church also features a lovely set of cloisters – something of a rarity in densely-built Venice. In recent years, the vineyard has resumed wine production, selling bottles under the label Harmonia Mundi.

San Pietro di Castello

Always wary of Roman interference, Venice literally kept papal representatives as far from the city center as possible. All the way out on the island of San Pietro di Castello, the church of the same name was the city’s official cathedral until 1807. Besides Palladio’s façade, the church features a Veronese and some early Christian artifacts. The snow-white bell tower originally had a dome on top.

Practicalities

Staying in Castello

We stayed near Santi Giovanni e Paolo on a previous trip, which provided easy access to the big sites in San Marco. The Campo Santa Maria Formosa’s central location would also be ideal for most visitors. For those who don’t mind extra travel time, the neighborhoods beyond the Arsenale offer a less-touristed version of Venice.

Transportation

The 4 and 5 vaporetto lines serve all stops in Castello. On the Riva degli Schiavoni, the San Zaccharia stop also serves the 1 (to train station via Grand Canal), B (to Giudecca or Lido), and 7 (to Murano, seasonal) lines. For details, see the map of all vaporetto lines linked on the official website.

Further Reading

Donna Leon’s beloved Brunetti series uses the police procedural format to explore contemporary Venetian life. Castello appears frequently, as the location of both the Questura (police headquarters) and the hospital.

Our other posts on Venice include:

Staying in Santa Croce, Venice’s Most Authentic District

Cannaregio, Venice’s Most Relaxing District

Venice’s San Polo District: The Rialto and Beyond

A Guide to Venice’s Eclectic and Historic Churches