Lucca and Pisa: A Tale of Two Romanesque Cities

Once upon a time, two Tuscan city-states grew rich from trade. They used their wealth to build a slew of cathedrals, towers, piazzas, and palaces in their own unique version of the Romanesque style.

A bit of context: when the Roman Empire fell apart, so did building techniques throughout most of Europe. Over time, the Christian church became a dominant force in society, financially as well as culturally. Architecture’s re-emergence, not surprisingly, focused on churches. Romanesque architecture encompasses a huge range of localized styles and regional crafts, with some delightfully quirky concoctions.

In Pisa and Lucca, this meant capitalizing on the proximity of the Carrara mountains with their exquisite white marble. Traders brought back inspiration from Byzantine mosaics as well as intricately worked Islamic surfaces. Tuscany’s growing prosperity supported a community of artisans who produced increasingly creative fusions of Mediterranean traditions. The two city-states developed a style using row upon row of columns with blind arches, giving plenty of opportunities to showcase local carving.

Romanesque Architecture, Part I: Lucca’s Eclecticism

Lucca lies near the Serchio River, in a lush valley surrounded by the green Carrara mountains. Its medieval walls have been converted into a park which offers views of the historic center as well as the landscape around it. Inside the walls, you’ll find one atmospheric piazza after another. The streets are medieval in scale, but never cramped.

Lucca’s historic buildings are scattered throughout town, which is small enough to wander without fear of getting lost. Part of the fun here comes from never knowing what you’ll see next and discovering interesting details tucked away. For example, the Guinigi tower has a grove of ancient oak trees sprouting on top. The Piazza dell’Anfiteatro derives its oval shape from a past as the site of a Roman amphitheater. The San Martino Cathedral has a labyrinth embedded in the right pier of the portico. On the Basilica of San Frediano, an elaborate golden mosaic covers the entire upper facade, contrasting with the simple white expanse below.

Lucca’s Romanesque churches are special favorites of mine because they are so playful: stacks of columns in every shape and color, plus animal statuary galore. They remind me of being a kid in the candy store who’s told it’s ok to pick one of everything. Perhaps the best examples are the facades of the San Martino Cathedral and the San Michele in Foro, both of which feature tiers of colored, carved, patterned columns, each one unique.

Local legend says the cathedral’s collection originated in a contest for the best column: instead of awarding a winner, the townspeople decided to use them all. Whether or not that’s true, the one-of-each approach shows up in other places, such as the bell tower with a different number of openings on each level (a feature typical of Italian Romanesque).

Up close, the play continues with details like the small lion statues perched on top of pilasters inside the portico of the cathedral, each one smiling down at us in its own particular way.

Medieval Italian buildings feature stripes extensively and sometimes wildly. Ancient Romans pioneered the use of stripes both in a structural sense and as decoration. In Lucca, striped buildings date back to the ninth century. They seem to be everywhere in the historic center – even opposite our hotel.

Visiting Lucca

Lucca’s train station is across the street from the old city. The walls are about 4 km in circumference, with everything inside no more than a few minutes’ walk away. We fell for Lucca’s charms several years ago, and returned for five days this year. Look out for our upcoming post on this lovely town.

Romanesque Architecture, Part II: Pisa’s Elegance

You can’t do justice to Pisa on a hot day. Like Florence, Pisa straddles the Arno River, and many of the most scenic views can be found along its elegant sweep. Also like Florence, Pisa does not have much by way of greenery. This makes it easier to appreciate the beauty of the buildings, which include no less than five museums and three major churches along its banks. However, the openness exposes you to the elements. When we visited, temperatures were in the 90’s with no breeze; we found the riverfront empty in the late morning.

The Piazza dei Miracoli consists of a carpet of grass surrounded by walls, with the cathedral, baptistry, and tower (you know, the one that leans) right in the middle. I initially assumed the name refers to something religious, but it actually comes from writer Gabriele D’Annunzio, who called the site a prato dei miracoli (“meadow of miracles”) when he saw it from an airplane in 1910. Apparently he liked the contrast between the lawn and the marble. We were more preoccupied with the heat radiating off the grass. There were few places to sit and no shade whatsoever. On the positive side, the simple layout highlights the architecture, which is distinctive enough to earn the name “Pisan Romanesque.”

Constructed between 1063-1118, the cathedral is the largest Romanesque church in Tuscany. The intricate but elegant design uses strict geometry to temper an abundance of decoration. With its white-on-white color scheme and bordered edges, it almost looks like it’s made of paper.

The Renaissance did not happen overnight in Florence, but developed over several centuries across much of Italy. Pisa’s cathedral seems to presage the humanist rebirth and advent of the modern age. In the 11th century, Pisa was arguably the most powerful city-state in the peninsula. Maritime activity exposed its citizens to a wide range of cultures and environments, which they incorporated into their influential cathedral complex. From the rows of arches on the outside to the bands of charcoal gray on the inside, it brings together ancient Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic elements.

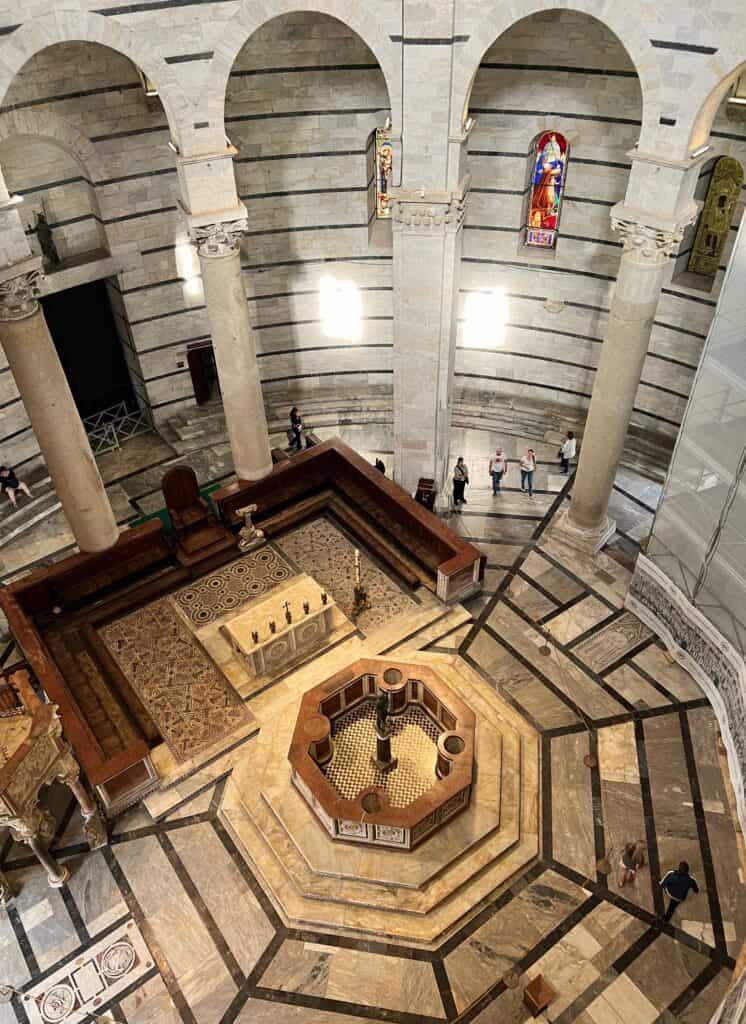

The huge circular baptistery was begun in 1152, and remains Italy’s largest. A strange half-tile, half-lead roof tops the intricately-carved marble walls. Inside, stripes wind endlessly around the walls and floor. The round shape also channels sound, as demonstrated every half hour when a staff member sings a few notes to demonstrate the acoustics.

Nicola Pisano’s influential baptistery pulpit of 1255-60 marks the beginning of Renaissance sculpture. After visiting the ruins in Rome, Pisano began mixing classical elements with the more ornate style used in Catholic churches at the time. He adopted ancient Roman subjects (a naked Hercules sandwiched between two saints) and pieces from the ruins themselves (the pulpit columns from Ostia Antica).

The Leaning Tower’s exceptional angle draws a different kind of attention. Construction began in 1172, with an alarming tilt emerging after just a few years. The Pisans persevered, giving the ground long breaks to settle between each addition and even making one side taller. When the angle reached 5.5 degrees in 1990, the tower closed to the public. Engineers spent 11 years stabilizing the tower without eliminating the iconic tilt (which is now back to four degrees). After all, this ‘failure’ turned the tower into one of the most iconic pieces of architecture in the world.

The Camposanto (cemetery) wasn’t begun until 1277, and demonstrates how the Pisan Romanesque continued to adapt. Designed like a monastic cloister, it has columns and framed openings carved in the delicate Venetian Gothic style, but here topped by round arches in the Roman tradition. Along with the tombs of distinguished citizens, the arcade also holds a collection of ancient Roman funerary monuments and carvings. Meanwhile the walls feature extraordinary frescoes from the 14th century, ranging from a target-shaped map of the cosmos to the devastations of the plague. A few are surreal enough to rival Hieronymous Bosch.

We recommend the “Complete” ticket, which includes the Duomo museum as well as the monuments mentioned above. Unless you plan to climb the tower, you probably won’t need to reserve tickets online. See the website for more information.

Visiting Pisa

Pisa makes an excellent day trip. The main train station, Pisa Centrale, lies south of the river, about 25 minutes’ walk from the Piazza dei Miracoli. We used the Pisa San Rossore station, which is just a few blocks from the cathedral complex.

Most don’t venture beyond the cathedral complex and Leaning Tower, but there is plenty more to see. The Botanical Garden offers an antidote to the grass carpet in the Piazza dei Miracoli. Or you can head to the pedestrian Borgho Stretto, a portico-lined street full of shops and dining options. Between them lies the Renaissance-era Piazza dei Cavalieri, once the city’s political center and now home to one of the country’s most prestigious universities.

More Romanesque

For a different kind of Italian Romanesque, see our posts on the Striped Cathedrals of Orvieto and Siena and the striped architecture of Verona.